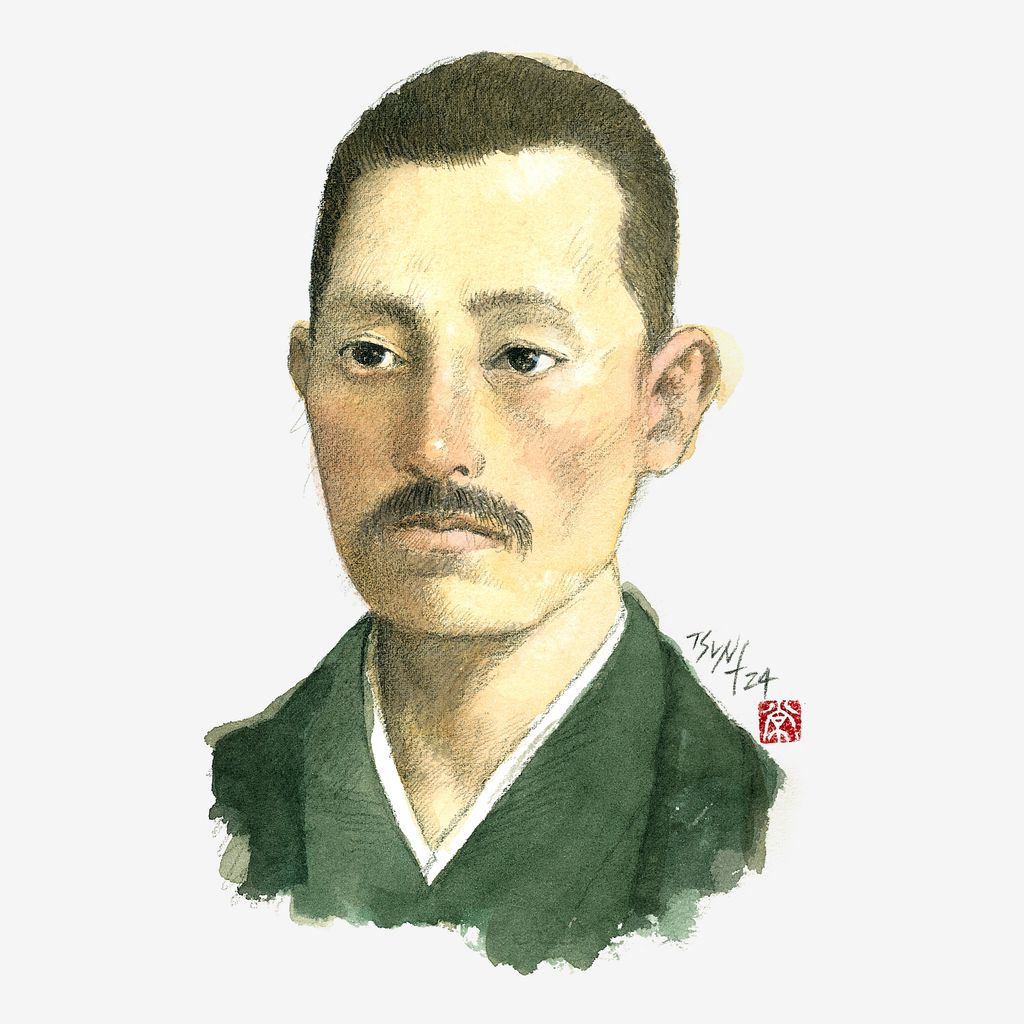

Mizuno, Toshikata

水野年方

Japanese Painter and Printmaker1866–1908

Mizuno Toshikata was a ukiyo-e artist and nihon-ga painter of the Meiji period. Best known for his bijin-ga prints depicting elegant ladies in historical and contemporary settings, his diverse work also included kuchi-e illustrations, musha-e warrior prints, senso-e war prints and historical nihon-ga paintings. Toshikata was active in various art circles such as the Nihon Kaiga Kyōkai and trained many outstanding artists, including Kaburagi Kiyokata.

Mizuno Toshikata was a versatile artist who bridged Japan’s artistic traditions across the tumultuous Meiji period. Trained by the ukiyo-e master Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, he distinguished himself with newspaper illustrations, kuchie-e for literary magazines, historical musha-e warrior prints, and sensō-e propaganda prints visualizing the Sino-Japanese War. Toshikata’s talent came to the fore in his numerous bijin-ga prints depicting elegant ladies in historical and contemporary settings. Although Toshikata mainly produced woodblock prints, he also developed a strong interest in historical nihon-ga painting.

Toshikata stood out as an artist who thrived in both the commercial market and the academic art scene. Through his involvement with various art groups, especially the Nihon Kaiga Kyōkai and the influential Bijutsu-in, Toshikata had an active voice in shaping the development of modern Japanese art.

Toshikata trained many young artists, including Kaburaki Kiyokata and Ikeda Shōen, who became significant artists in their own right.

Though his career was cut short at 42, his influence endured through his artistic output and the accomplishments of his students.

Early life

Kumejiro Nonaka, later known as the artist Mizuno Toshikata, was the son of a master plasterer. His mother left them soon after his birth, and he was raised by his father and stepmother. Born in 1866 just two years before the Meiji Restoration, Toshikata was part of the first generation of children to enjoy (compulsory) public schooling.

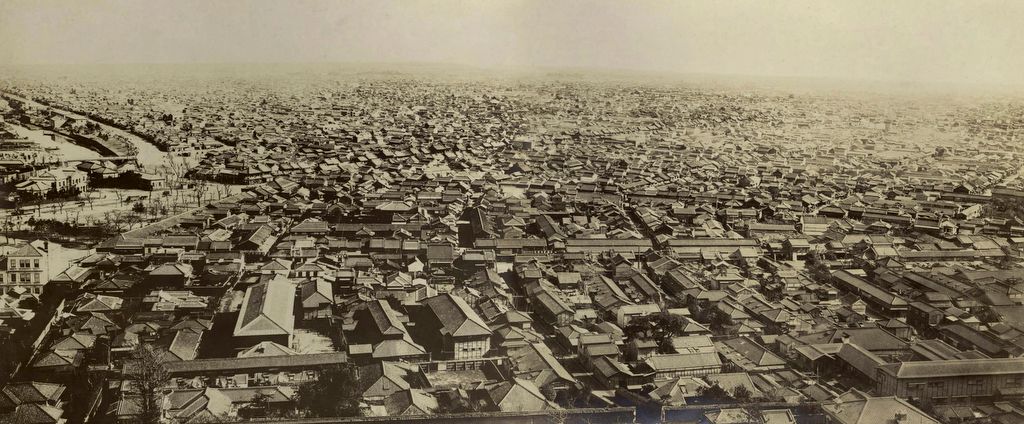

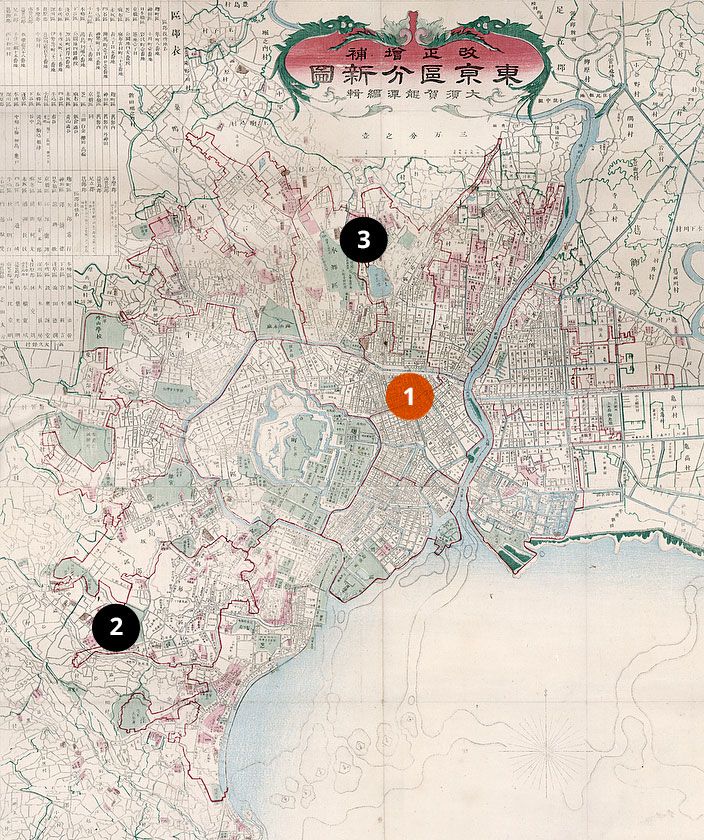

Toshikata grew up in the Higashi Kon'ya-chō sub-district of Kanda, a bustling area in the heart of Edo — the city that would soon be renamed Tokyo. Together with Nihonbashi and Kyobashi, the Kanda area was part of the Shitamachi (or Lower Town) forming the downtown center of Edo. The busy streets were lined with merchants and craftsmen, and the neighborhood where Toshikata lived used to have many dyers, giving the area its name: Kon'ya-chō, meaning “dyer’s shop town.”

As a young boy, he frequently helped out at his father’s workshop. When a friend of his father noticed Toshikata drawing flowers and birds into wet plaster with a trowel, he was impressed by the boy’s artistic ability and encouraged him to pursue painting.

Toshikata’s father hoped he would someday take over the family business. But when his son confessed, “I really want to be an artist,” he let him pursue his passion. When Toshikata turned 14, his father even arranged an apprenticeship with Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, one of the best-regarded ukiyo-e artists of the day.

Training ground

In 1879, Toshikata began his training under Yoshitoshi, moving into his teacher’s house. It was common for Japanese artists to live with their apprentices to facilitate learning through close observation and hands-on learning. His teacher was known by the nickname “Bloody Tsukioka Yoshitoshi” — earned for crafting disturbingly violent, yet very popular, ukiyo-e works. Eimei nijūhasshūku (“Twenty-eight famous murders with verse”) was a particularly gruesome example.

Unfortunately, Yoshitoshi also showed a violent temper in his real life. He was a strict instructor who treated students harshly, both verbally and sometimes physically. Yoshitoshi also began to neglect his pupils. A notorious playboy, he was rumored to spend his days in pleasure quarters instead of properly teaching his students.

The two artists were living in unstable times, as Japanese society was reinventing itself in the wake of the Meiji Restoration of 1868. As this modernization pushed ahead, ukiyo-e went out of fashion, leaving the woodblock industry in dire straits.

Yoshitoshi, who had achieved great popularity and critical acclaim as an ukiyo-e master, was also affected by these difficulties. In 1872, a few years before Toshikata became his student, Yoshitoshi suffered a nervous breakdown. He then developed severe depression, lived in poverty, and stopped all artistic production. He resumed work a year later, and business had recovered by the time he took on Toshikata as his apprentice. However, alternating periods of success and poverty plagued him for the rest of his life. Toshikata’s harsh experience in Yoshitoshi’s workshop may have been rooted in the pressures his teacher faced.

Eventually, the antics of the famed ukiyo-e master proved too much for Toshikata’s father, and the training was cut short. A year into his apprenticeship, his father made him quit and took Toshikata home.

New influences, and a return

And so, Toshikata returned home to work at his father’s workshop. Unfortunately, his father passed away soon after. Then only 16, Toshikata moved in with his stepmother’s relatives, the Ino’okas, who ran a pottery business. There he found the opportunity to sketch decorations for their porcelain products to support himself financially. In another silver lining, he met his first wife, Fusa, the Ino’oka’s youngest daughter.

Still aspiring to become a painter, Toshikata took lessons from two artists of the Nan-ga school, a genre influenced by Chinese litarati painting. He first studied with Shibata Hōshū and later Yamada Ryūtō, who also taught him porcelain painting.

Meanwhile, Toshikata’s former teacher, Yoshitoshi, regained his footing and resumed painting. In the fall of 1882, he exhibited a painting titled Yasumasa Yasusuke-zu at a Meiji government-sponsored art show, receiving critical acclaim. Based on this work, the following year Yoshitoshi created a woodblock triptych, an extraordinary example of ukiyo-e at its finest.

Seeing the masterpieces of his teacher seems to have reminded Toshikata that his heart, too, was in ukiyo-e. He resolved to quit porcelain painting and return to Yoshitoshi to resume his apprenticeship. Initially, the master refused to take him on. But Toshikata showed resolve; no matter how harshly Yoshitoshi rejected him, he refused to give up his efforts. Eventually, Yoshitoshi relented and let him rejoin the school.

Upon Toshikata’s return, Yoshitoshi had only four apprentices left working under him. Apparently, not all of the students could handle the pressure of their eccentric master. This time, however, Toshikata knew what he was signing up for and proceeded to distinguish himself through hard work, quickly gaining Yoshitoshi's trust. The teacher developed a special fondness for the young artist and would later designate him as his successor.

First triumph

When Toshikata turned 19, his teacher gave him the opportunity to make his debut as an artist. Until then, he had done some small works as an assistant; now his master trusted Toshikata to execute a large commission, allowing him to sign it with his own name.

He was to create a multicolored triptych woodblock print depicting a dramatic scene from The Tale of the Heike, an epic account of the power struggle between rival clans for control of medieval Japan.

Toshikata rose to the occasion with the spectacular debut, Sasaki Moritsuna Bizen no kuni Fujito no watari ni Heigun o osowanto gyojin ni mizu no senshin o tou zu (“Sasaki Moritsuna Asking Fisherman to Reveal the Shallows Where His Troops can Cross and Attack the Taira Forces at Fujito in Bizen Province”). Toshikata had emerged from the shadow of his master. Published in 1884, this was probably the first nishiki-e to bear the signature, “Mizuno Toshikata.”

Following his debut work, Toshikata created a series of three nishiki-e woodblock prints titled Setsu-getsu-ka (“Snow, Moon, and Flowers”), which depicted scenes based on The Tale of the Heike, set in the late 12th century. Toshikata developed a special interest in historical subjects and would later create many works featuring such themes.

Finding his niche

Mizuno Toshikata was part of a generation that started their careers as woodblock print artists at an unfortunate time. As discussed, he was born into a period when ukiyo-e was declining in popularity, and traditional woodblock printing was being replaced by letterpress and lithography techniques.

But these modernizations of the Meiji era also heralded the rise of new media — like newspapers, magazines, and mass-produced novels — and new opportunities for work emerged with them. Toshikata and his teacher managed to venture into the evolving publishing industry by creating illustrations for books, seizing new avenues for income.

Drawing on his experience depicting historical themes, Toshikata created illustrations for many works of historical fiction. Through these commissions, he built a reputation for book illustrations.

When the daily newspaper Yamato Shinbun launched in 1886 (Meiji 19), Mizuno Toshikata participated as an illustrator alongside his master. In addition to current events, the paper also carried serialized novels, entertainment, and gossip articles — equivalent to the tabloids of today.

He drew many illustrations for Yamato Shinbun, together with his master Yoshitoshi. In 1887, through the latter’s recommendation, Toshikata joined the newspaper as an illustrator, which offered him a stable income. This marked the start of a prolific career as an independent artist.

End of an era

In 1892, while Toshikata was working at Yamato Shinbun, his longtime teacher passed away. Often considered the last great ukiyo-e master of the Edo period, the death of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi marked the end of an era.

Since Yoshitoshi had named Toshikata as his successor, there was speculation that the student might assume his teacher’s name. But this did not come to fruition, likely because it was uncommon for painters or printmakers to do so (as it was in other professions, such as kabuki acting). Instead, Yoshitoshi passed on his name in the traditional manner of composing a “go” for his student: When the time came for his pupil to make his debut, he took on the final character of his master’s name, “-toshi,” to produce “Toshi-kata.”

As for Toshikata’s family name, it was originally Nonaka. After his father's death, Toshikata decided to change his family name to Mizuno to avoid military conscription. Along with the public schooling initiated by the Meiji government came graver obligations: Many were sent to fight on the expanding borders of the new Japanese Empire, and the prospect of being drafted into action was not everyone’s cup of tea. A calmer front was the recently annexed island of Hokkaido, where hard-working men were sent to harvest the rich natural resources and work in agriculture. Those who developed the northern island were exempt from military service — thus it became popular to buy one’s way into the family register of a qualified person to avoid being drafted. The novelist Natsume Soseki was another famous example who used this trick.

Art from the front lines

In 1884, the First Sino-Japanese War broke out, an intense conflict in which the Japanese Empire forcefully challenged China’s influence over Korea. Naturally, Japan’s newspapers turned the successes of its military campaigns into a propaganda-fueled media spectacle that captured the attention of the masses craving after news from the front lines.

The First Sino-Japanese War was a significant moment for news publishing in Japan, transforming the landscape of journalism and shaping public opinion. On the one hand, it led to advancements in reporting techniques, visual media, and printing — while at the same time highlighting the emerging nationalistic tendencies in journalism and a tension between freedom of the press and government censorship.

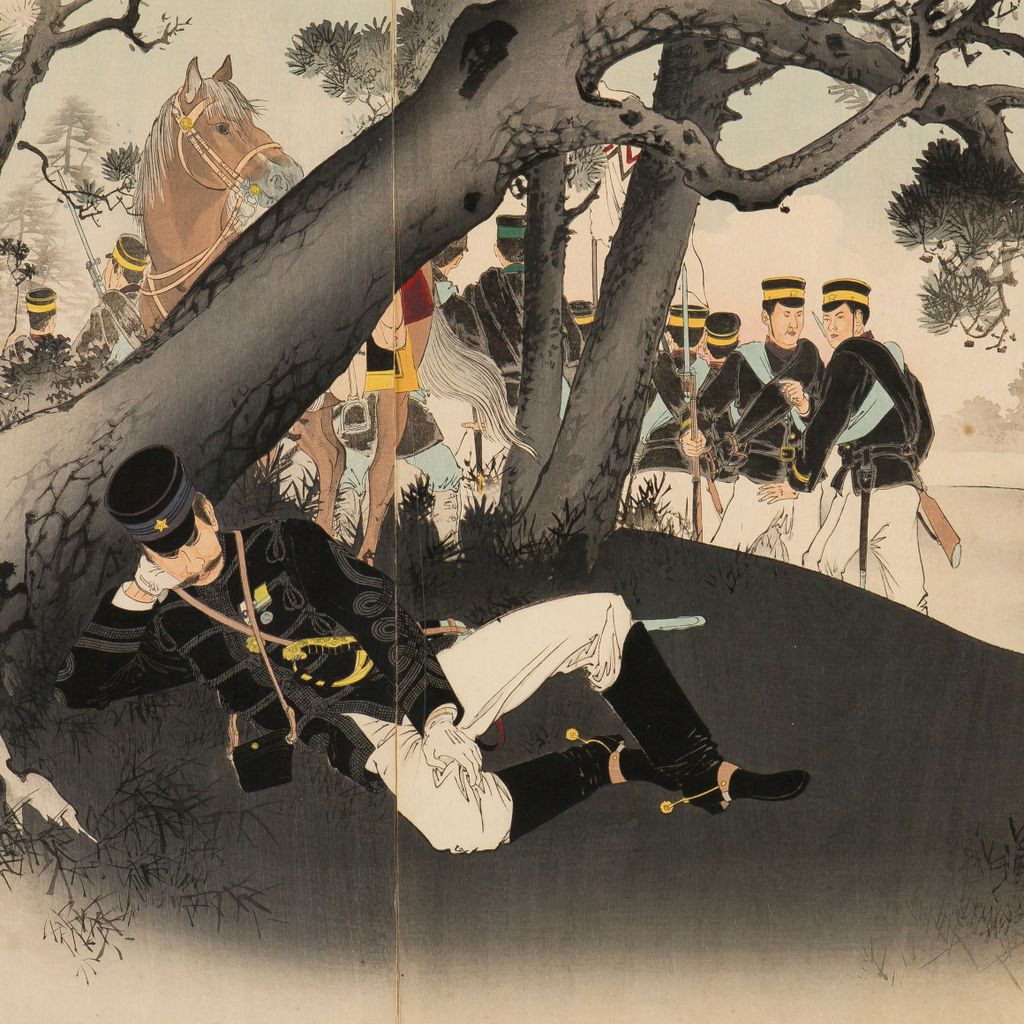

For the woodblock print industry, the war meant an unprecedented surge in demand for a new genre of prints, the sensō-e (literally, war-pictures), while marking at the same time the last, yet still-vibrant breath of a dying art form. While the genre was competing with faster and less expensive technologies, such as lithography and photography, publishers quickly recognized the demand for dramatic visuals that could illustrate the war’s developments and capitalize on the opportunity to make money.

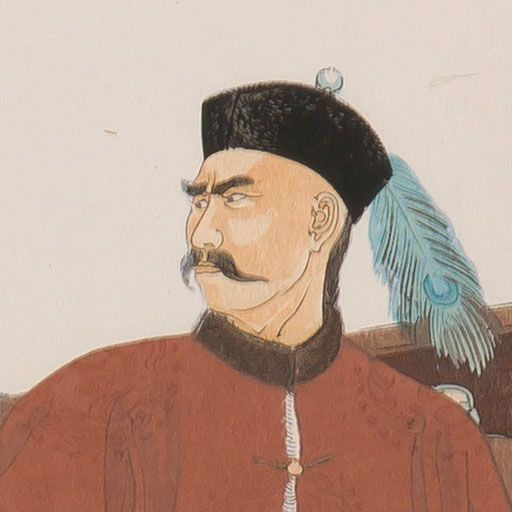

Even though photography had emerged as a key journalistic medium, it was not yet widely available. The black-and-white reproduction in some ways lacked the fidelity and excitement offered by a dramatically composed multicolored woodblock print. War prints typically included scenes of battles fought by the Japanese army with modern battleships and weapons — as most of the audience quite literally had never glimpsed these technologies — or portraits of high-ranking officers and courageous soldiers.

Though most of the sensō-e were based on real events, reported in “real-time” from the frontlines, print designers frequently exaggerated the skirmishes they depicted, both to emphasize Japanese heroism and military might and entice buyers of woodblock prints. Patriotic citizens were eager to purchase these works, and the competition between publishers over customers was intense.

Although the First Sino-Japanese War lasted less than a year, it produced around 3,000 woodblock prints depicting scenes from the conflict — a staggering amount meaning that, on average, some 10 new prints were published daily.

Toshikata became one of the many woodblock-print artists recruited to produce sensō-e war pictures. With prior experience depicting historic war heroes, he was well suited to bring the war’s dramatic battle scenes to life.

Various publishers, such as the prominent Akiyama Buemon and Sekiguchi Masajirō, who specialized in catering to the sensō-e craze, sought out Toshikata’s services. He created several elaborate triptych prints, including “Naval Officers Discussing Strategy for the Conquest of Qing” and “Hurrah and Hurrah Again for the Great Empire of Japan,” which showed the battle of Pyongyang.

These commissions must have been a welcome source of income for Toshikata, who ended his stint at Yamato Shinbun just before the war began — providing financial stability at a time when traditional ukiyo-e was declining in popularity. But as the battlefield dust settled in 1895, the demand for woodblock prints dissipated as well. For Toshikata, it was time to turn the page and focus on other creative endeavors.

The literary frontispiece

When the literary magazine Bungei Club was launched by publishing firm Hakubunkan in 1895, Mizuno Toshikata was hired to contribute illustrations. Over the course of nearly 40 years, Bungei Club would become a literary staple, playing a significant role in shaping modern Japanese literature and culture. It published the works of major writers such as Higuchi Ichiyo, Izumi Kyoka, and Kunikida Doppo.

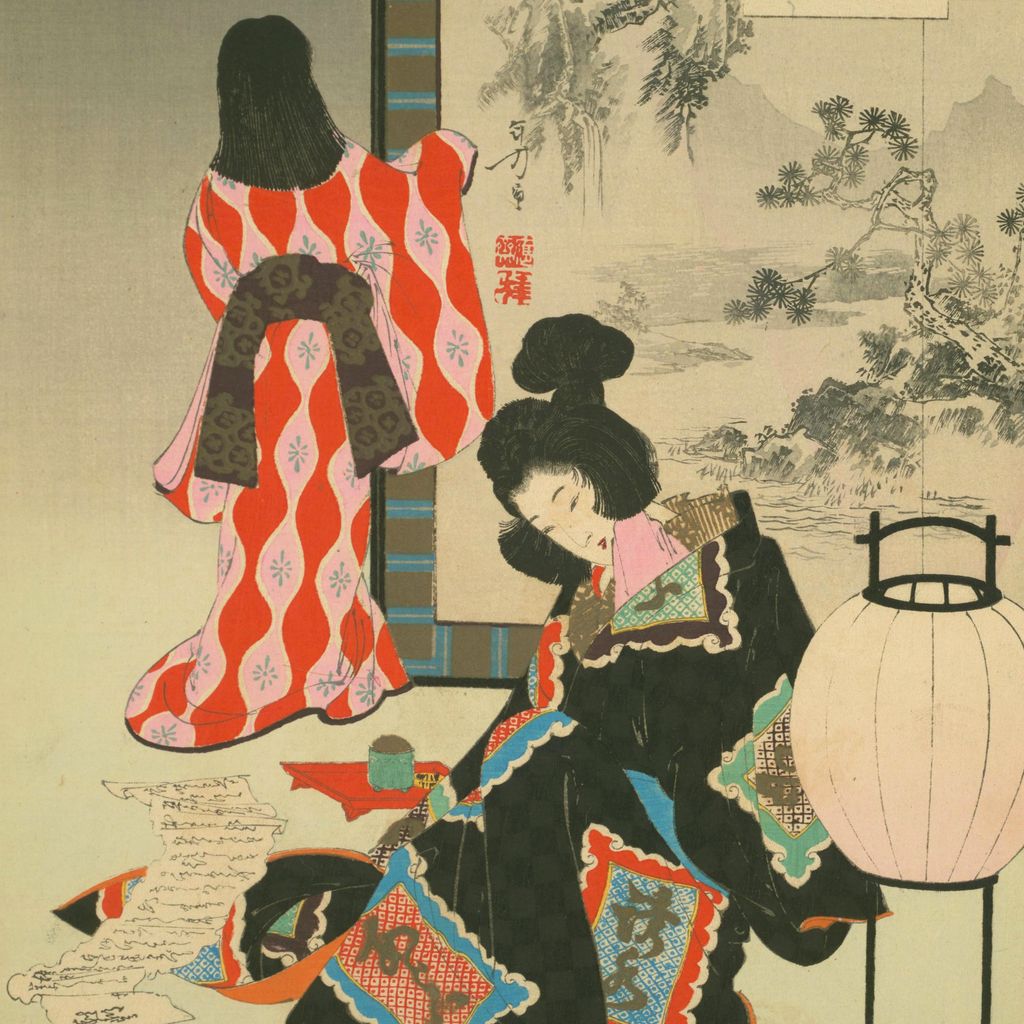

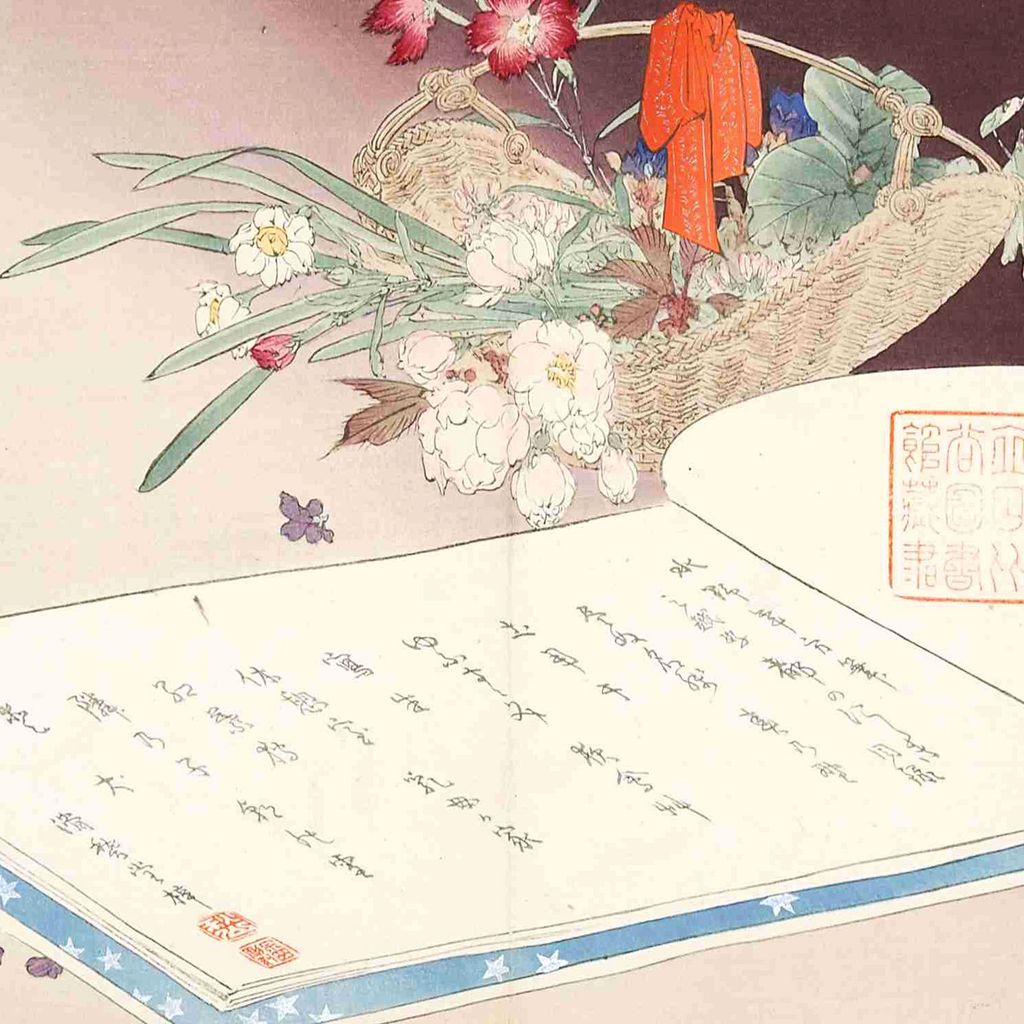

Early Bungei Club issues resembled paperback novels about the size of an A5 pocketbook, featuring collections of novellas. Each issue included a “kuchi-e” frontispiece illustration. These kuchi-e became very popular with readers and a ubiquitous feature of all the literary magazines of the time, used to visualize the main story of the issue.

These woodblock prints (or, later, lithographs) were printed on separate sheets and usually folded once or twice to fit into the publications they accompanied. Very popular with readers, kuchie-e served as an important promotional tool to increase sales of novels and magazines.

Drawing on his experience as an illustrator for Yamato Shinbun, Mizuno Toshikata was responsible for creating kuchi-e frontispiece illustrations for a large number of issues. He illustrated famous works and authors such as “The Operating Room” and “Oizuru Soushi,” by Izumi Kyoka, “The Organ of Colors” by Iwaya Sazanami, “Saigyo Aizuma” and “Yume Gatari” by Kōda Rohan, “Unagi dan'na” by Yamada Bimyō, and “Oyakokoro” by Futabei Shimei.

It is fascinating to see how Toshikata was able to adapt his style to the audience of his commission. The delicate lines, soft colors and gentle female figures of his kuchi-e illustrations contrast sharply with the intensity of his early work and the bombast of his senso-e propaganda prints, showing the wide range of expression in his repertoire.

Toshikata’s beautiful kuchie-e illustrations were well received. Coupled with his diligent attitude, they earned him the reputation of an illustrator whose work could determine book sales. Toshikata would work for Bungei Club for 13 years, until his passing. He drew 52 kuchi-e during this period, making him one of the most prolific contributors to the magazine.

An eye for beauty

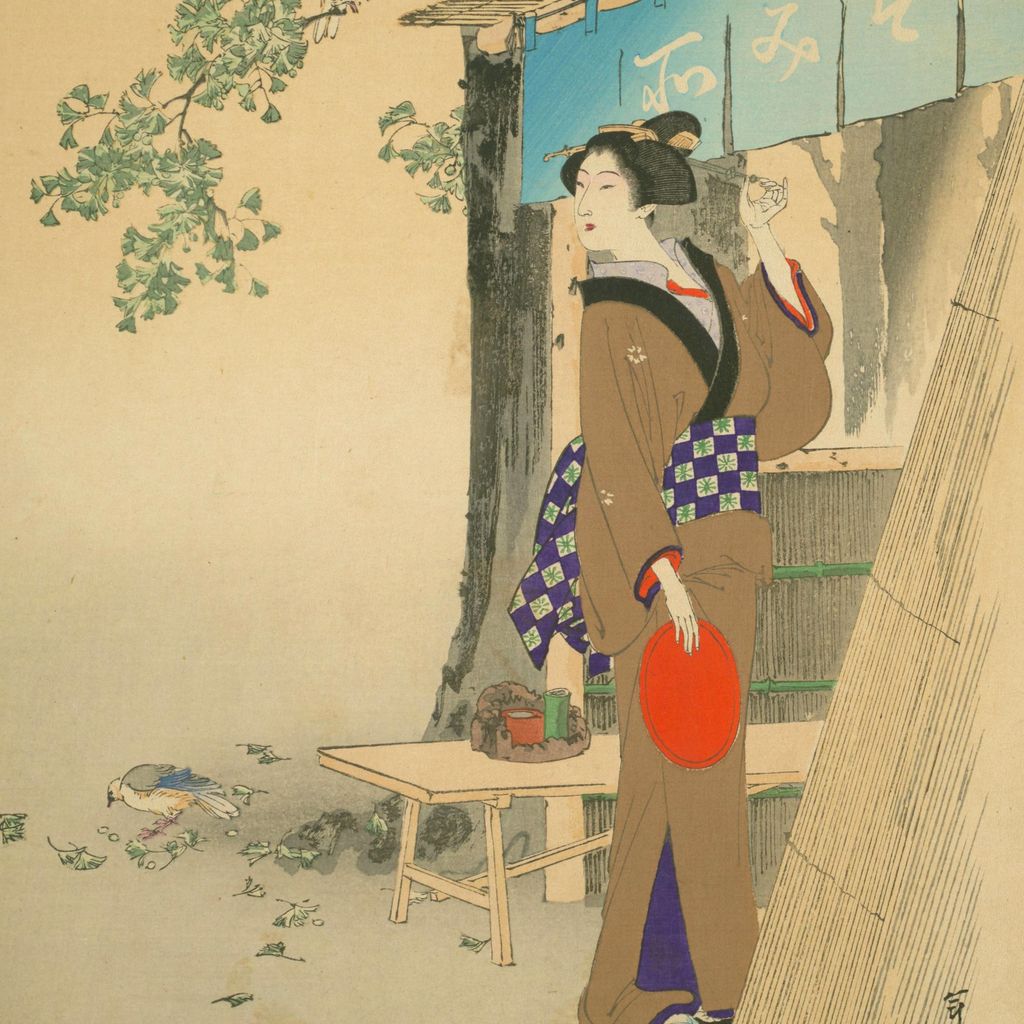

Elevated by the success of Toshikata’s kuchi-e illustrations, which largely centered around gentle female figures, Toshikata became famous for his bijin-ga, or “pictures of beautiful women.”

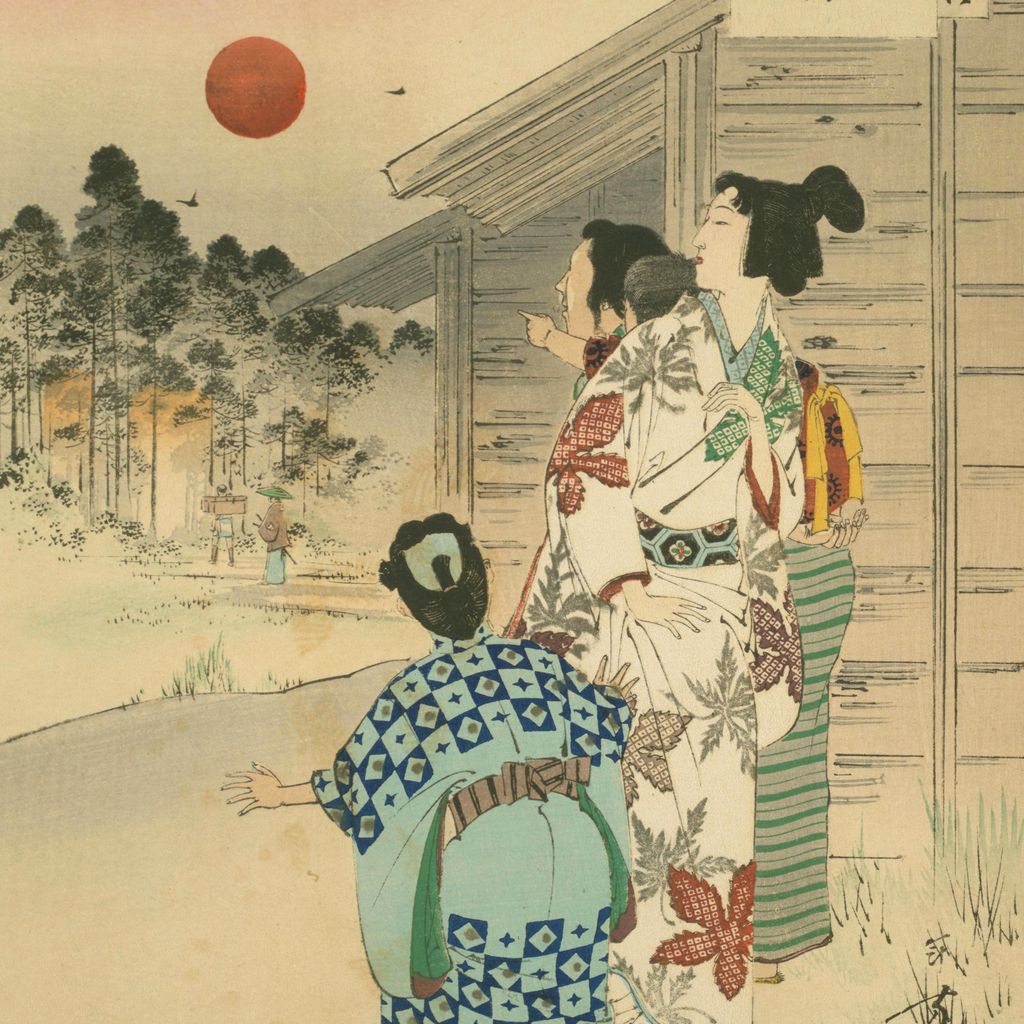

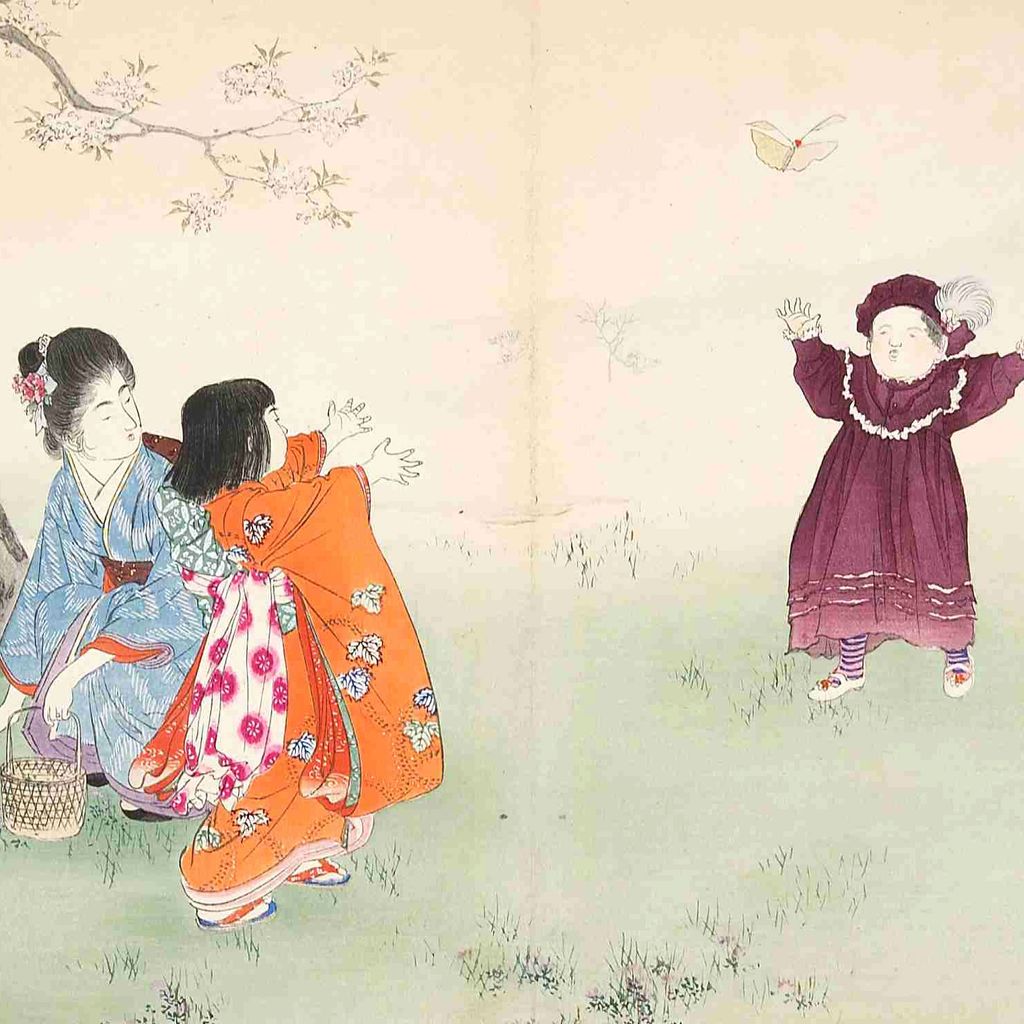

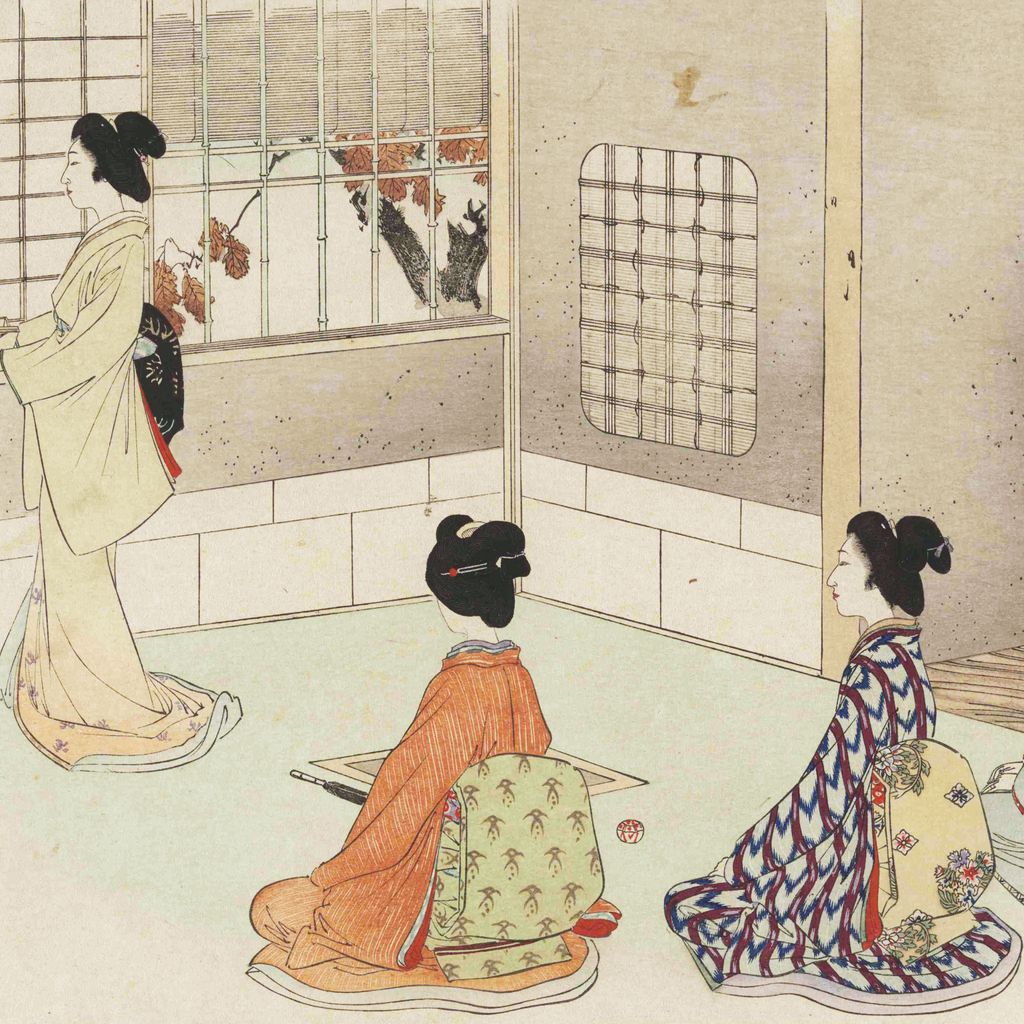

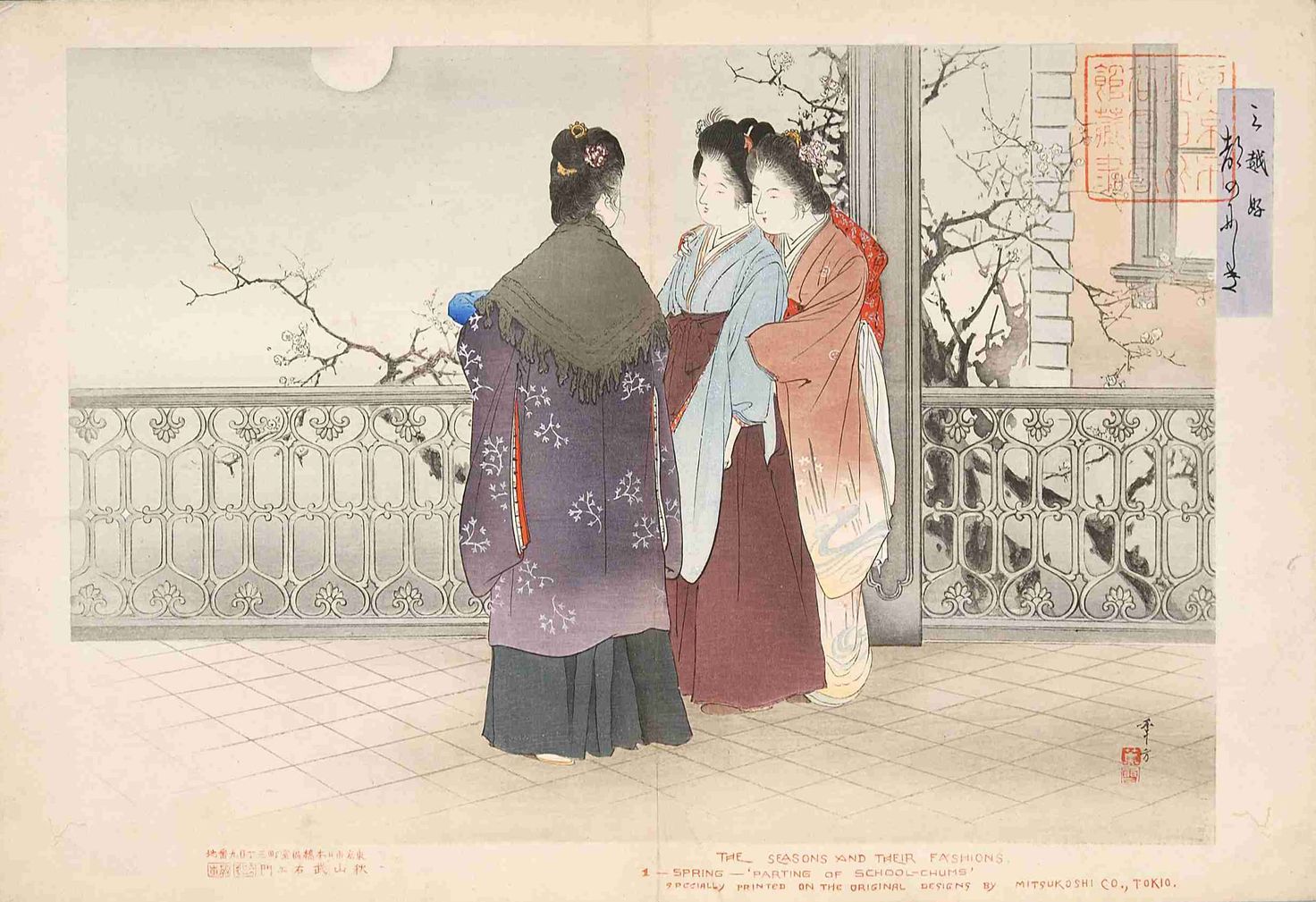

Even today, Toshikata is perhaps best-known for his bijin-ga prints, in particular his later works set in medieval periods. Some of his earlier works also portrayed contemporary women of his time. For example, in 1893, while still working with Yamato Shinbun, the Mitsui Department Store (now known as Mitsukoshi) commissioned Toshikata to design a series of woodblock prints called Mitsui Gonomi Miyako no Nishiki to advertise their modern kimono collection. In 12 scenes, with a set of three dedicated to each season, Toshikata portrayed young ladies and children in casual activities, aptly dressed for the time of year.

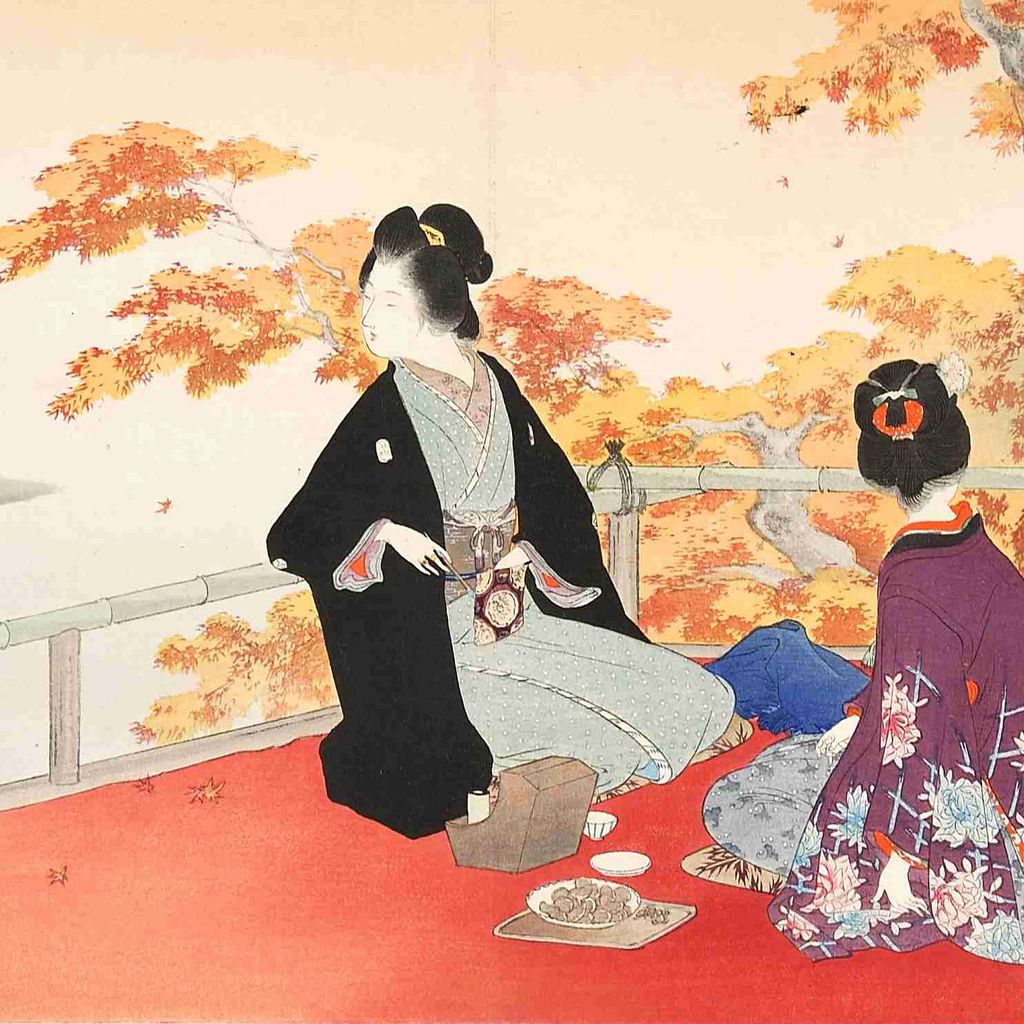

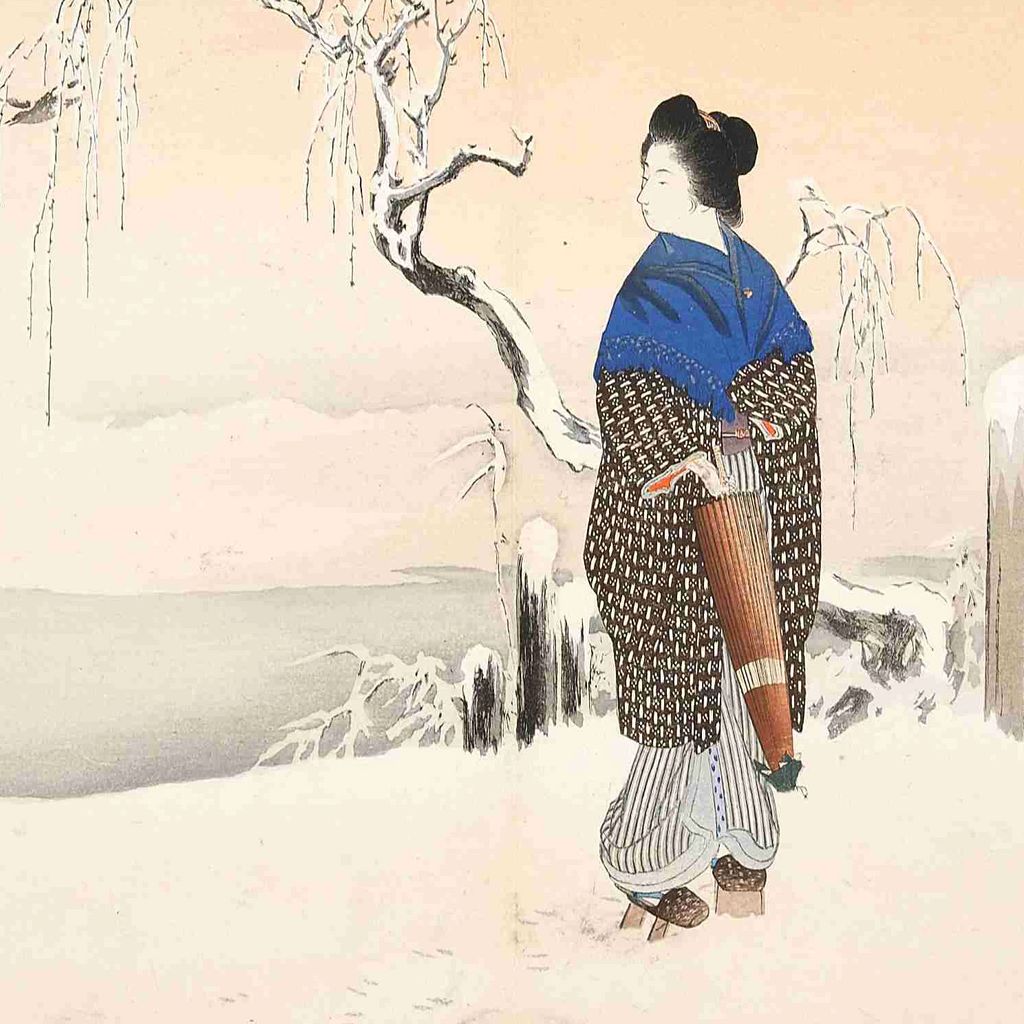

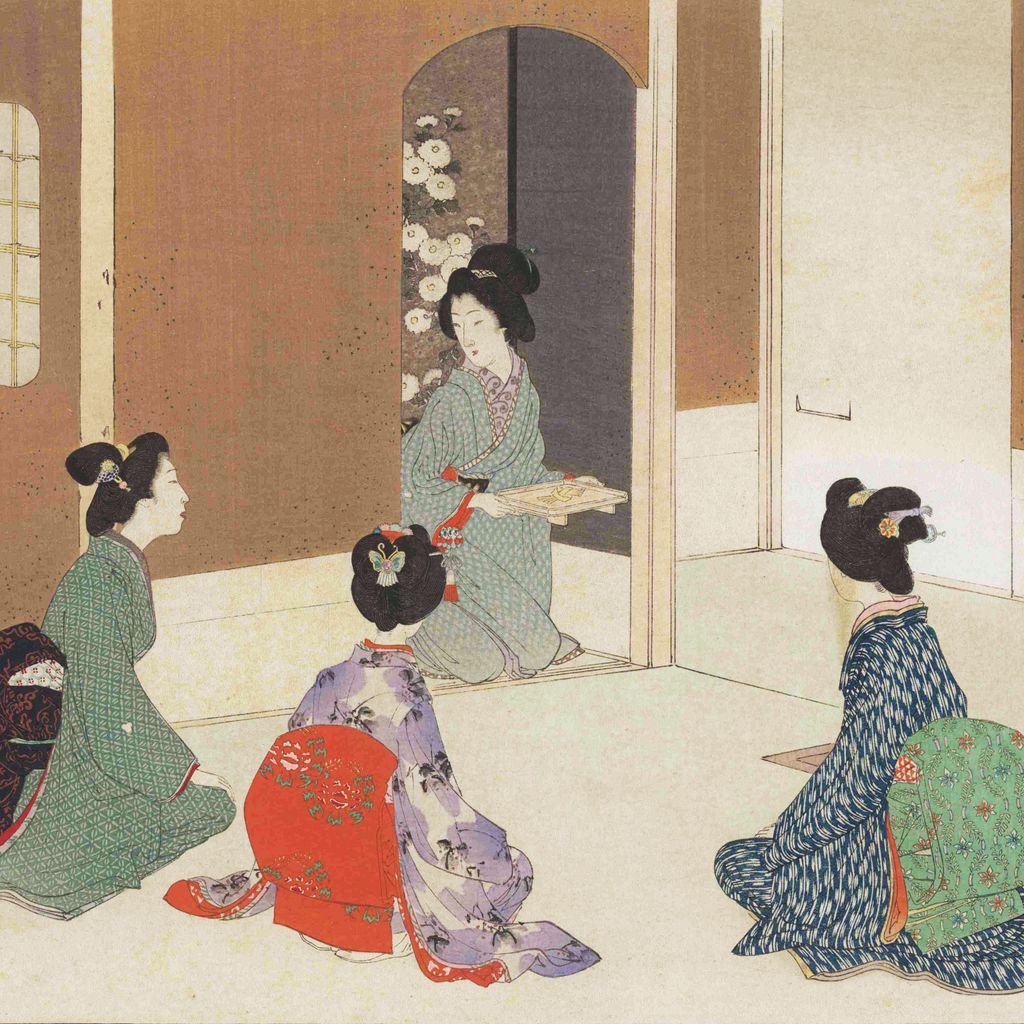

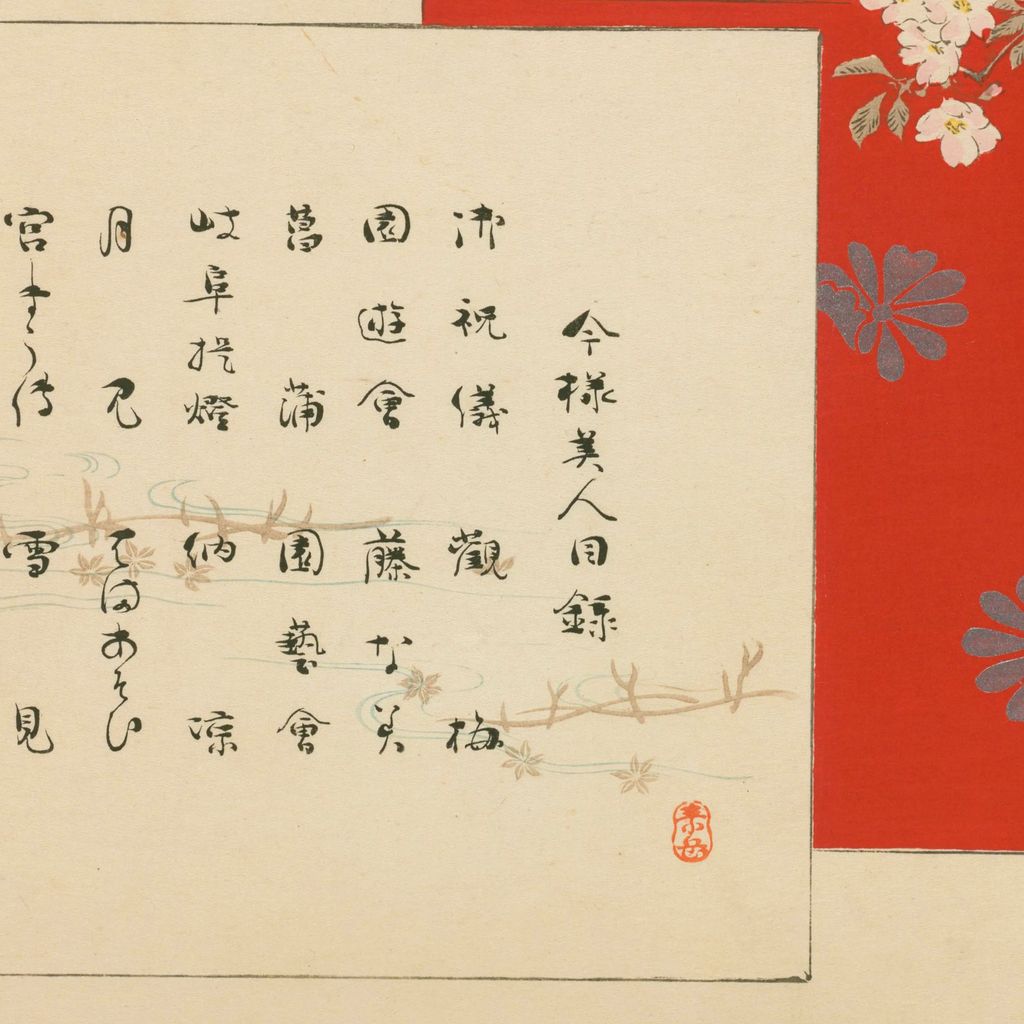

While he was hired to create the commercially lucrative war propaganda prints, he created a beautifully serene woodblock series called Imayo Bijin, in which “present-day beauties” enjoy pastime activities. Published in 12 installments starting in 1897, each print depicts a different seasonally themed motif for each month.

His series Cha no yu nichinichi gusa portrays a group of ladies enjoying a chanoyu tea gathering. The sequence of 16 prints follows the hosts throughout the day, from the preparations in the early morning to the arrival of three guests and their departure in the evening.

In all of his bijin-ga works, Toshikata pays close attention to women’s fashion. His splendidly detailed portraits offer a glimpse into their lives and beauty ideals, and highlight the changing gender roles of women during a transformative period in Japanese history. In addition, his scenes subtly capture the Western-style accessories, architecture and furniture that reflect the growing Western influence on Japanese society in the late 19th century.

A passion for history

According to the memoirs of Kaburaki Kiyokata, a student of Toshikata's, historical subjects where his greatest passion. Indeed, Toshikata dedicated a large portion of his oeuvre to such subjects.

His most famous work, Sanjuroku-kasen (“Selection of Thirty-six Beauties”), is a prime example. In this woodblock print series created over the course of three years, he depicts elegant women from different historical eras. The earliest one depicts ladies from the ancient Nara period, and others the Kamakura, Muromachi and Edo periods.

This masterpiece exemplifies Mizuno Toshikata’s attention to detail and historical accuracy, as he sought to capture everything from the clothing and hairstyles of the time to background props. He thoroughly researched the historical settings of his works, especially the traditions of the medieval Japanese Imperial Court.

Toshikata asked the nobleman Matsubara Sukehisa to give him lessons in yūsoku kojitsu, the study of the etiquette and traditions of the Court. Then, in 1902, Toshikata co-founded the Rekishi Fūzoku Gakai (“Society for Historical Genre Painting”) with Imperial Household Artist Kobori Tomoto and historical scholar Seki Yasunosuke, in order to exchange notes with like-minded artists.

While much of Toshikata's work centered on the bijin-ga theme, he also was interested in historical epics and musha-e — a ukiyo-e genre that depicts battle scenes and heroic armored warriors. For example, Nankō fushi sakurai-eki ketsubetsu no zu (“Lord Kusunoki Masashige Bids Farewell to His Son at Sakurai Station”) depicts a poignant scene from The Taiheiki (“Chronicle of Great Peace”), a historical epic written in the late 14th century. The dramatic nishiki-e tryptych shows Lord Kusunoki Masashige, a renowned samurai, bidding farewell to his eldest son, who is about to leave for his final battle.

Other works, such as Genpei Setsu-getsu-ka no Uchi Yuki draw on The Tale of the Heike, which recounts the events of the Genpei War fought in the 12th century. With all his passion for Japanese history and attention to detail, it is perhaps not surprising that Toshikata collected antique weapons and armor and used them as references for his work.

The new Japanese painting

Woodblock prints were Toshikata’s primary medium. However, he also painted: From the 1890s onward, most of his works shown at art exhibitions were historical paintings.

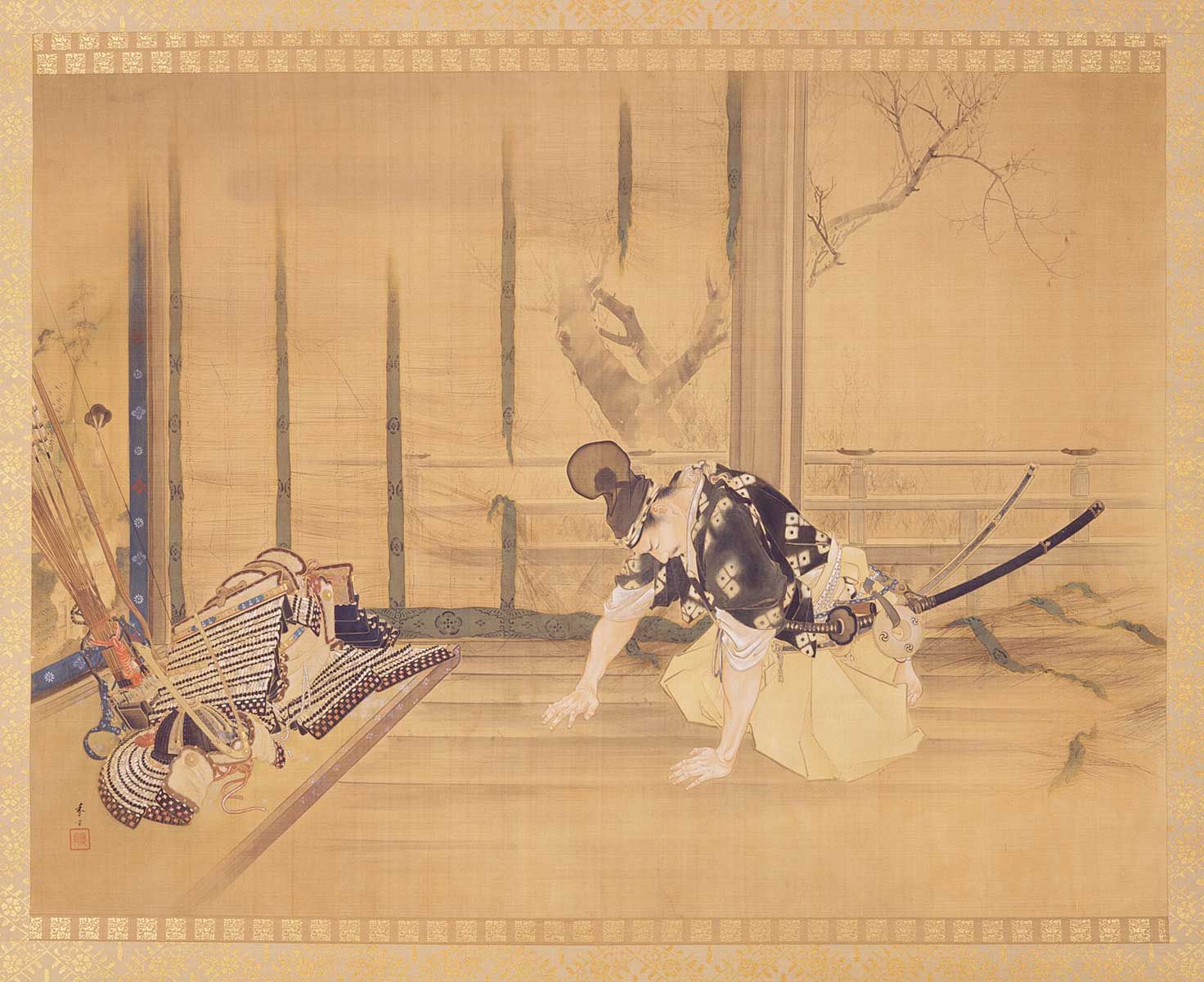

Among them was his nihon-ga painting, Sato Tadanobu Sankan Zu (“Attendance at the House of Sato”). It shows a scene of the Gikeiki, a medieval gunki monogatari war tale (known as “Chronicle of Yoshitsune” in English). The painting was displayed at the first exhibition by the Nihonga-kai art group in 1898. Following the show, Toshikata had the honor of presenting the painting as a gift to the Imperial Household Agency.

With the sweeping cultural changes brought about by the Meiji Restoration, Japanese art was also at a crossroads. The art that had flourished in the Edo period fell by the wayside, giving way to new forms. But what shape the new would take was not yet clear. Art was divided into nihon-ga, or Japanese art, and yō-ga, or Western art — concepts introduced in the Meiji period to define the country’s art by establishing different genres. In reality, the lines were quite blurred, with Japanese painting techniques used for Western subjects and vice versa.

Toshikata had the opportunity to learn from various masters in genres like nanga or ukiyo-e; these had since passed their heights of popularity, and he seemed to be concerned about their place in modern art. Indeed, he firmly believed that the artistic value of ukiyo-e was worth preserving.

In 1891, he joined the Nihon Seinen Kaiga Kyokai (Japan Young Painters Association), a group of 10 young artists led by Okakura Tenshin who were on a mission to rethink the boundaries of genre and redefine modern Japanese painting. Subsequently, a group of students from the Tokyo Fine Arts School became part of the forum, including Yokoyama Taikan, who would later rise to prominence as a leading figure in the art world. In 1896, the group changed its name, becoming simply the Nihon Kaiga Kyoukai (Japan Painting Association). The same year, they held their first painting exhibition, partnering with the Hakuba-kai painting society. It consisted of three categories: works in traditional styles, works in the Western style and works that attempted to develop new styles.

The group held exhibitions every year until 1903. Toshikata contributed several works to most of these exhibitions, for which he regularly won prizes — the first one in 1898 for Yūgure (“Dusk”) and the last one in 1903 for a pair of hanging scrolls entitled Tachibana no Hayanari no Musume (“Daughter of Tachibana no Hayanari”) and Hino Kumawaka, which depicted calligraphers and scenes of filial piety from the early Heian period.

Okakura Tenshin, whom Toshikata met through the Nihon Kaiga Kyoukai, served as director of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, which he had helped to found. Tenshin was a vocal defender of Japan's traditional art forms against the “excessive” Westernization of the early Meiji Restoration. In 1897, disapproving of the school’s disproportionate emphasis on European painting methods, he resigned as director. He then founded the Nihon Bijutsu-in (Japan Arts Institute) with Hashimoto Gahō, Yokoyama Taikan, and 37 other artists. They sought an approach balancing the study of traditional Japanese painting schools and the active adoption of Western painting techniques, to foster the development of painting that was both modern and Japanese.

These ideas resonated with Toshikata. In 1898, Tenshin invited him to participate in the fledgling Nihon Bijutsu-in as well, and he became a special supporting member.

Around the same time, in 1897, Toshikata also helped to start the Nihonga-kai (Society for Japanese Painting), where he became a board member and exhibition juror. Most of the founding members of the Nihonga-kai were former members of the Japan Painting Association, who left because they had different artistic ideas and were unhappy that the group’s exhibitions seemed to favor students from the Tokyo Fine Arts School. Toshikata remained an active member of both groups, as well as the very progressive Nihon Bijutsu-in. In a way, he maintained common ground between them in the expanding spectrum of the Nigon-ga art scene.

Then, in 1902, Toshikata became a founding member of the Rekishi Fūzoku Gakai (Society for Historical Genre Painting) led by Kobori Tomoto, also a former teacher at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts who had resigned to form the Nihon Bijutsu-in with Tenshin. Through the Rekishi Fūzoku Gakai, Toshikata came into contact with other kuchi-e artists, such as Kajita Hanko, and prominent nihonga painters, such as Shimomura Kanzan and Yasuda Yukihiko.

As Mizuno Toshikata enjoyed commercial success, making woodblock prints on commission and creating kuchi-e illustrations for various publications, he was able to pursue his creative passions and participate in academic art groups. Through his involvement in these contemporary circles, Toshikata had an active voice in shaping the canon of Japanese art, helping rehabilitate and preserve the status of genre prints and works of the ukiyo-e school.

To the heart of the Tokyo art scene

In 1886, when Toshikata completed his apprenticeship with Tsukioka to work for Yamato Shinbun, he set up his art studio in a warehouse that had belonged to his late father. The house, adjacent to his childhood home in Kanda Kon'ya-chō, still contained his tools and hearths, a reminder of his father and his work as a plasterer. Toshikata converted a room on the second floor, where he would work and teach one of his earliest apprentices, Kaburaki Kiyokata.

Kiyokata was only 13 when he joined him in 1891. He did not live with Toshikata, as was customary for apprentices, but instead attended classes under him after school. Still, the room was rather small to both work and hold classes. When Toshikata was working on a large artwork, he would either have to cancel the class or choose a day when his apprentice was not there. Furthermore, as the popularity of Toshikata’s work increased, so did the number of students. At its height, Toshikata was teaching six students. Kiyokata remembers that the desks were arranged facing each other with the sensei's desk in the center, so even walking around the small room was difficult.

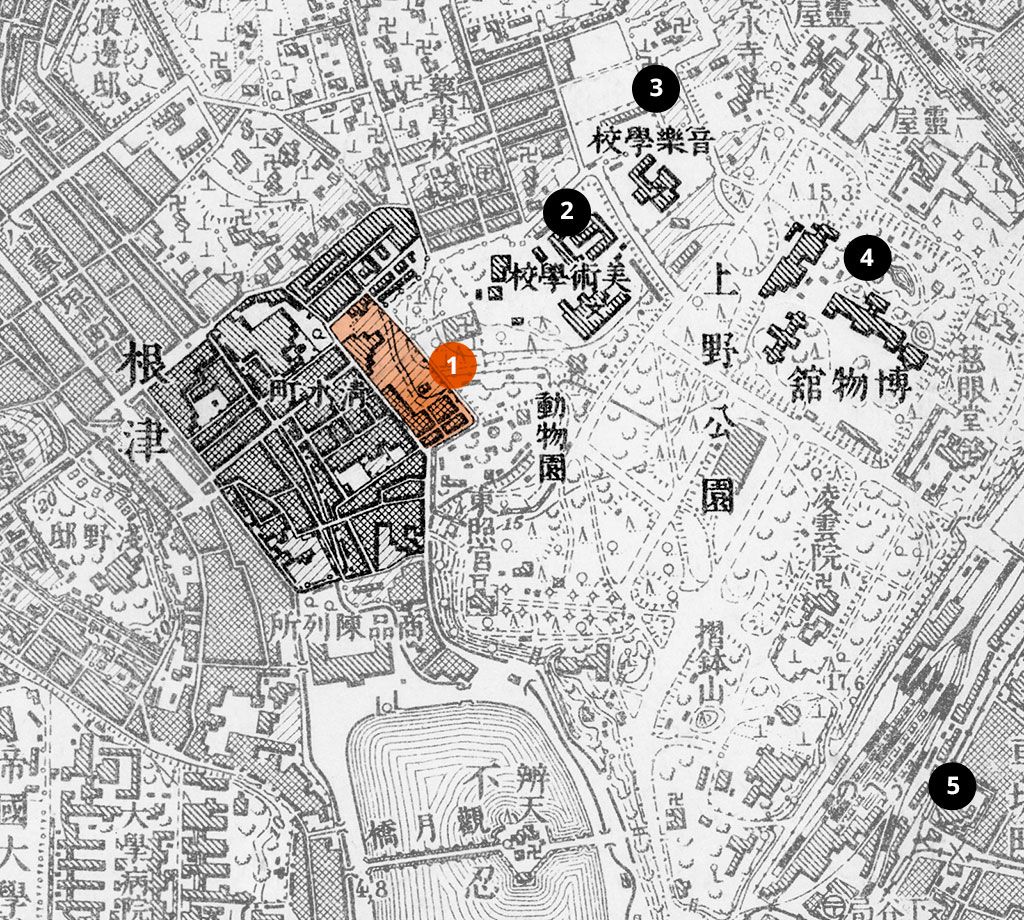

After working in the converted warehouse for nine years, Toshikata was hard pressed to find a better location. Finally, he found a plot of land to build an appropriate house designed to his needs as an artist and to further develop his private art school. In May 1895 he moved out of his childhood home in Kanda Kon'ya-cho and moved to Yanaka Shimizu-chō, located just north of Ueno.

In the 1890s, Ueno was a vibrant and rapidly developing area of Tokyo, becoming a significant cultural hub. Multiple museums, including the predecessor of the Tokyo National Museum, were already operating. Just a few years before Toshikata moved there, the Tokyo Fine Arts School (now the Tokyo University of the Arts) opened in 1887, attracting artists and intellectuals.

Incidentally, when the Nihon Bijutsuin was founded in 1898, it built its institute in Toshikata's neighborhood of Yanaka. Adjacent to the main building were built eight two-story thatched buildings, the “Yanaka Hachikenya,” where artists and their families lived. Among the artists living in the Yanaka Hachikenya were Kobori Tomon and Shimomura Kanzan, with whom Toshikata later founded the Rekishi Fūzoku Gakai, and Yokoyama Taikan, who was a fellow member at the Nihon Kaiga Kyoukai.

Toshikata had found himself a neighborhood full of like-minded artists, intellectuals and circles, with whom he would collaborate and exhibit paintings. Given that his house was located within a 10-minute walk of the Tokyo Fine Arts School, it must helped him attract students to his private art school, which was known as the Keisai Ga-juku (Keisai Painting School).

Tragically, shortly after he moved to Yanaka, his wife Fushimi died of typhoid fever. Kiyokota, the artist’s student, recalls Fushimi in his memoirs as a kind-hearted soul who would bring afternoon tea and snacks to their atelier, holding conversation in a warm and relaxed atmosphere.

A living legacy

Alongside his collaborations with peers in the contemporary art scene, Mizuno Toshikata did much to shape the future of modern Japanese painting through his work with students — many of whom went on to become significant artists in their own right.

Kaburaki Kiyokata

Kaburaki Kiyokata was one of Toshikata’s first apprentices. He was the son of Jōno Saigiku, one of the founders of the Yamato Shinbun newspaper that employed Toshikata. Influenced by his father, a distinguished man of letters who also wrote plays and theater reviews, Kiyokata grew up surrounded by literature. He enjoyed reading novels — admiring the kuchi-e illustrations that came with them — and aspired to become an artist himself.

And so, through his father’s introduction, Kiyokata became a student of Mizuno Toshikata in 1891. At the time, Toshikata was 26 years old, still relatively young to take on a pupil. Kiyokata himself was only 13, and began attending classes at Toshikata’s studio after school. After a year, Kiyokata was convinced he wanted to be an artist, so he left high school to learn full-time with Toshikata.

After two years of diligent study, Toshikata trusted his talented pupil to succeed him at the Yamato Shinbun and take over the illustrations. Under his teacher’s instruction, Kiyokata created a large number of kuchi-e and became one of Japan’s leading nihon-ga artists, famous for his bijin-ga paintings. In 1924, he was named an Imperial Household Artist; 30 years later, he was awarded Japan’s Order of Culture for his many years of contributions to the art world.

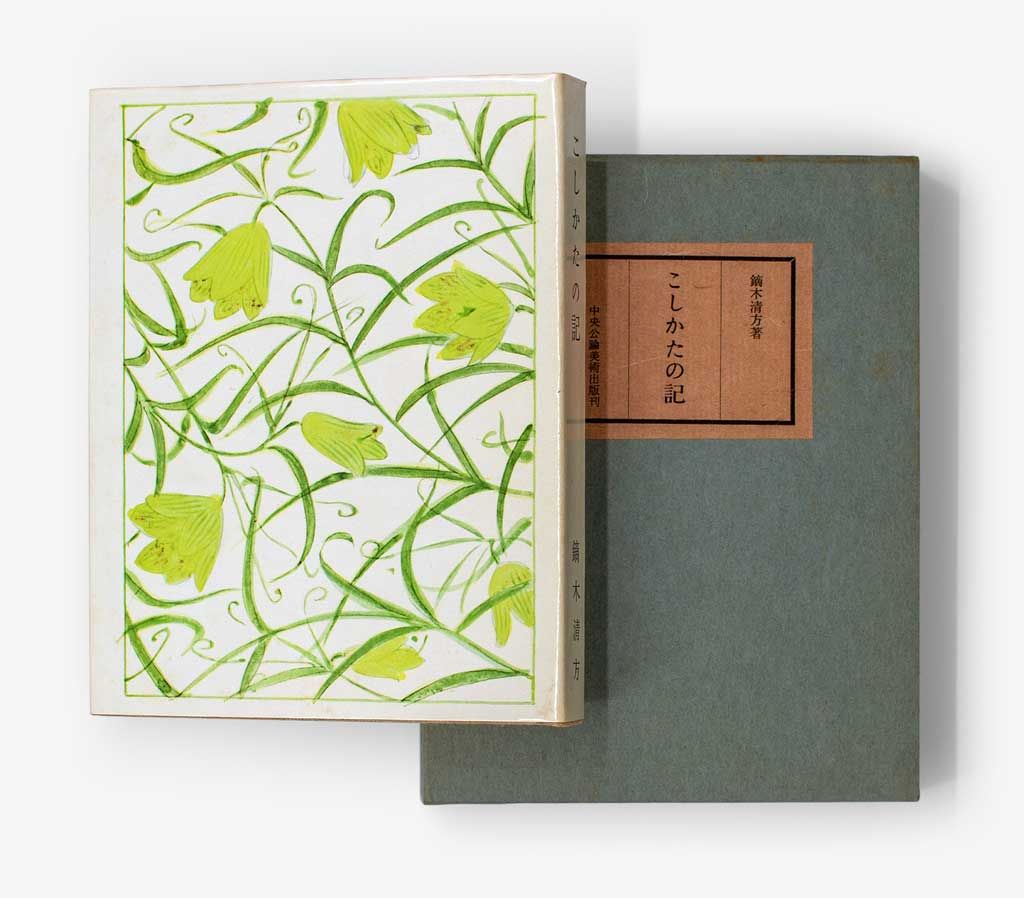

Kiyokata left detailed notes on Mizuno Toshikata’s teaching, which he described as very gentle — perhaps a reaction to the harsh style Toshikata himself had endured under Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. And it is thanks to Kiyokata’s 1961 memoirs, Koshi-kata no ki, that we know many anecdotes about Toshikata’s life. It is clear from every piece of his writing that Kiyokata deeply respected his master as a person and an artist.

Ikeda Terukata

Ikeda Terukata became an apprentice of Mizuno Toshikata in 1895, four years after Kiyokata.

Later, he formed the Ugō-kai group with Kiyokata, Shōen, and others. Also a prolific kuchi-e illustrator, he created works for the novelist Izumi Kyouka and became a nihon-ga artist, specializing in portraits and genre paintings.

Arai Kanpō

In 1899, Arai Kanjurō became an apprentice of Toshikata, who gave him his art name, “Kanpō.”

Like his teacher, Kanpō was particularly drawn to historical paintings. After studying with Toshikata, he worked on copying Buddhist paintings for the magazine Kokka and was exhibiting in the early Bunten exhibitions. His career took a significant turn in 1916, after traveling to India, when he began to focus on Indian-style Buddhist paintings. In later years, his expertise in historical Buddhist paintings became highly regarded, and he participated in important conservation initiatives. For example, he was involved in a 1939 project to restore the murals in the Kondō, or Main Hall, of the Hōryū-ji Temple in Nara, one of the world’s oldest surviving wooden structures.

Ikeda (née Sakakibara) Shōen

Sakakibara Yuriko joined the ranks of Toshikata’s students six years later, in 1901. She was a great admirer of Uemura Shōen’s work, and Toshikata gave her the artist name “Shōen” to encourage her aspirations.

Only one year after beginning her studies, Shōen made her debut with exhibitions at the Nihon Bijutsu Kyōkai, the Nihon Kaiga Kyōkai and the Bijutsu-in. As her talent continued to win recognition and prizes at the Bunten exhibitions, she became known as “ Shōen of the West” — while her idol from Kyoto, Uemura Shōen, was called “ Shōen of the East.” She later married her fellow student, Ikeda Terukata.

Mizuno (née Ichikawa) Hidekata

Most fortuitously, in 1900, Ichikawa Kaya began her studies with Toshikata, who gave her the art name “Hidekata.”

Hidekata helped to paint the genre scenes that Terukata, Shōen, Kiyokata and other students of Toshikata produced. Notably, she also assisted Toshikata with creating Sato Tadanobu Sankan-zu, which was accepted by the imperial household.

Two years into her studies, she started to create her own paintings. In 1902, she showed Bijin (“A Beauty”) at a joint Nihon Kaiga Kyōkai and Bijutsu-in exhibition, receiving an honorable mention. For the next 10 years, she also worked on illustrations and frontispiece (kuchi-e) for Shōjo Sekai, Jogaku Sekai and other magazines.

In 1905, she married Mizuno Toshikata. When he tragically passed away just three years later, Mizuno Hidekata became the head of Toshikata’s school and was able to maintain it after his death.

“You who plays with art”

At the height of Toshikata’s activity, the publishing industry experienced an unprecedented boom, putting him in great demand for illustrations and kuchi-e. Toshikata was a very dedicated person and could not refuse any job offered to him — he is said to have been the artist who received the most commissions from publishers. While taking on more illustration work than he could handle, Toshikata also worked tirelessly on his painting projects.

In March of 1908 the artist collapsed from overwork while on a business trip. Mizuno Toshikata died a month later at the early age of 42.

His grave can be visited today at the Yanaka Cemetery, located north of Ueno in Tokyo, in the neighborhood where he last lived. His widow, disciples and associates also erected a monument in his honor on the grounds of the Myojin Shrine in his hometown of Kanda.

The monument’s inscription, written by journalist and art critic Seki Minejiro, reads:

Mizuno Toshikata, whose real surname was Nonaka and was commonly known as Kumejiro, was born in Kanda, Edo, in January 1866.

studied under Tsukioka Yoshitoshi and the arts of other schools

strove to further advance the art of ukiyo-e

of brushwork, highly refined and elegant

chosen to judge art exhibitions

Sato Tadanobu Sankan-zu, accepted by the Imperial Household

passed away on April 7th, 1908

only 43 years old

always kind and generous (or “yet of great compassion”)

with many disciples rich in talents

This monument shall forever commemorate his virtue

Ah, you who plays with art, enjoy its flowers and cultivate its roots

Although life is short, the fragrance of your flowers is eternal

Details

- Family Name

水野

Mizuno

- Given Name

年方

Toshikata

- Born

March 6, 1866

Tokyo, Japan

- Died

April 7, 1908

Japan, Tokyo

- Gender

- Male

- Nationality

- Japan

- Occupations

- Painter,

- Printmaker

- Fields of practice

- Woodblock Printing,

- Painting,

- Nihon-ga,

- Bijin-ga,

- Sensō-e,

- Kuchi-e,

- Ukiyo-e

- Alternative Names

野中 粂次郎

Nonaka, Kumejirō

Birth name

水野 年方

Mizuno, Toshikata

Art name

水野 粂次郎

Mizuno, Kumejirō

Adopted name

応斉

Ōsai

Art name

蔗雪

Shōsetsu

Art name

Selected

Works

Paintings

Prints

Artist

Sasaki Moritsuna Bizen no kuni Fujito no watari ni Heigun o osowanto gyojin ni mizu no senshin o tou zu

- Publisher:

- Akiyama, Buemon

Genpei setsugetsuka no uchi yuki

Abata denshichirō

Heijō gekisen Genbunmon kōgeki no sai…Harada Jūkichi

- Publisher:

- Sekiguchi, Masajirō

Dai-nippon teikoku banbanzai: Seikan shūgeki waga gun taishō no zu

- Publisher:

- Akiyama, Buemon

Genbumon kōgeki zuiichi gunkōsha Harada Jūkichi shi sento funsen zu

- Publisher:

- Akiyama, Buemon

Chinsen chihō nii gomei no Nihon kōhei Shinhei hyakuyonin gekitai

- Publisher:

- Matsuki, Heikichi

Sekkō kihei gunsō Kawasaki Iseo-shi hachigatsu mikka no yoru tanshin Daidōkō o eishō shite tekijō o shisatsu shi, tekishū ni jōshi yūzen kijun no zu

- Publisher:

- Sekiguchi, Masajirō

Ikaiei fukin ni oite waga kaigun rikusentai kesshitai shichi-yûshi senpô jôriku no zu

- Publisher:

- Akiyama, Buemon

Shinkoku hokuyō kantai i kai ni oite ei zenmetsu tsui teitoku teijoshō waga kaigun ni teki funō kantaku ni oite jisatsu zu

- Publisher:

- Akiyama, Buemon

Kato Kiyomasa taiseki o tenjite Orankai no kenjo o uchi-yabureru zu

- Publisher:

- Akiyama, Buemon

Genpei setsugetsuka no uchi tsuki

Fune no shuppatsu o miru bijin

Connections

- Relatives

- Nonaka, Kichigorō

Father

- Teacher of

- Arai, Kanpō

- Asano, Naokata

- Ikeda, Shōen

- Ikeda, Terukata

- Kaburaki, Kiyokata

- Kasahara, Tsunekata

- Koyama, Mitsukata

- Mizuno, Hidekata

- Nakayama, Shūko

- Ōno, Shizukata

- Satō, Kōhō

- Tajima, Sadakata

- Takeda, Keihō

- Watanabe, Hirokata

- Yamamoto, Nobukata

- Founding Member of

- Nihon Bijutsu-in

- Member of

- Nihon Bijutsu-in

- Nihon Kaiga Kyōkai

- Nihon Seinen Kaiga Kyōkai

- Nihonga-kai

- Rekishi Fūzoku Ga-kai

- Collaborated with

- Akiyama, Buemon

- Chizuka, Reisui

- Emi, Suiin

- Fukuchi, Ōchi

- Gakutei, Sadaoka

- Iwaya, Sazanami

- Izumi, Kyōka

- Jōno, Saigiku

- Katō, Satori

- Kawakami, Bizan

- Kobayashi, Kiyochika

- Kōda, Rohan

- Matsuki, Heikichi

- Minami, Shinji

- Murai, Gensai

- Murakami, Namiroku

- Nishida, Keishi

- Ōguchi, Rokubee

- Oguri, Kōichi

- Ōhashi, Otowa

- Ozaki, Kōyō

- San'yūtei, Enchō

- Sekiguchi, Masajirō

- Suzuki, Kason

- Takayama, Chogyū

- Takeda, Gyōtenshi

- Takeda, Heiji

- Tomioka, Eisen

- Tozawa, Masayasu

- Tsuboya, Zenshirō

- Tsukahara, Jūshien

- Udagawa, Bunkai

- Watanabe, Katei

- Yakkosuke, Inaoka

- Yamada, Bimyō

- Yoda, Gakkai