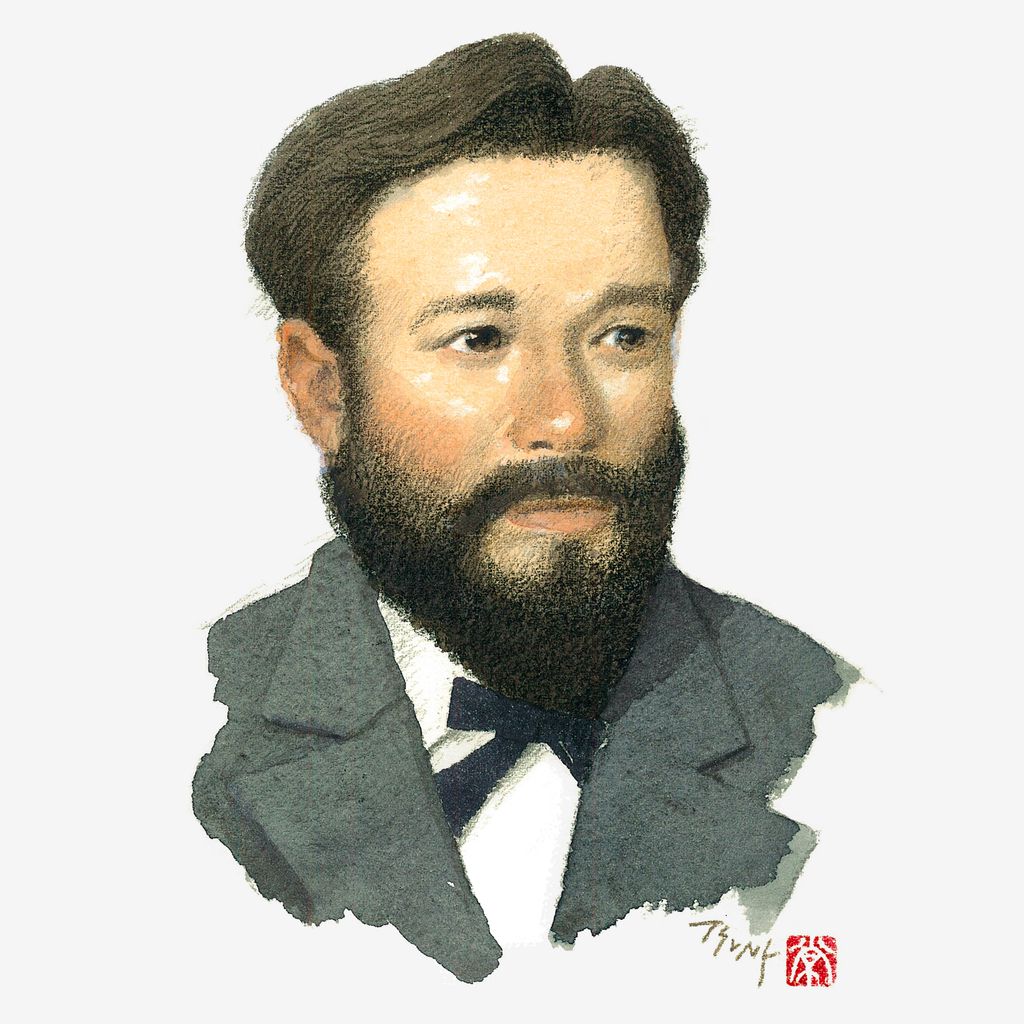

Hyakutake, Kaneyuki

百武兼行

Japanese Painter and Diplomat1842–1884

Hyakutake Kaneyuki was a Japanese diplomat and pioneering Western-style painter during the Meiji period. He was among the first Japanese artists to personally study Western painting techniques in England, France, and Italy. Remarkably, he became the first Japanese artist to have an oil painting showcased at an exhibition abroad, and he is credited with creating some of the earliest nude oil paintings by a Japanese artist.

Despite never working as a professional artist, Hyakutake Kanayuki was an early pioneer of Western-style painting in Japan. Serving as a diplomat in Europe representing the fledgling Meiji government, Hyakutake was among the first Japanese to study painting in person at the world’s leading art centers in London, Paris, and Rome, all while fulfilling his official duties.

Although he did not actively participate in the art circles in Japan upon his return, Hyakutake's experience in Europe and his artistic contributions enriched the early history of Western-style painting in the country. At that time, studying abroad was out of reach for most people. But Hyakutake's privileged upbringing and his role as an aide to the powerful Nabeshima family allowed him to pursue an education abroad. This opportunity laid the groundwork for his pioneering contributions to both art and diplomacy.

Early life

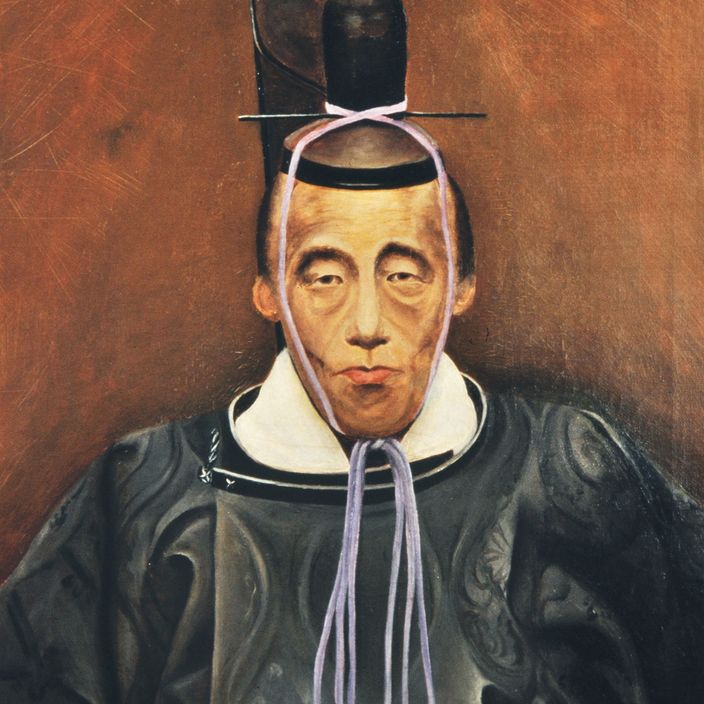

Hyakutake was born in 1842 into a family of samurai who served the Saga Domain. Coming from a family that was a senior vassal of the ruling Nabeshima clan, he was chosen at age eight to serve as a study companion to Nabeshima Naohiro, the heir who would eventually become the last Daimyō of Saga. This was the beginning of a lifelong friendship.

Although Nabeshima was four years younger, Hyakutake trusted him like an older brother and served as his close aide for the rest of his life. During his youth, Hyakutake is said to have been taught calligraphy and Bunjin-ga (literati painting) as well as Japanese and Chinese studies by Furukawa Matsune, a scholar of Japanese classics who worked for Nabeshima's father. In the early 1860s, around the age of twenty, Hyakutake received first English language lessons — a remarkably rare opportunity at the time.

A turn to the West

Nabeshima Naohiro succeeded his father as Daimyō in 1861, and he continued the latter’s progressive efforts to introduce Western science and technology to the Saga Domain. This included an educational focus on the dominant powers of the time, such as Dutch studies in the 1840s and English studies from the 1860s, as well as the development of steel refining, steam engines, and artillery. Even after Nabeshima’s appointment, Hyakutake continued to serve as his close assistant, accompanying him on official business.

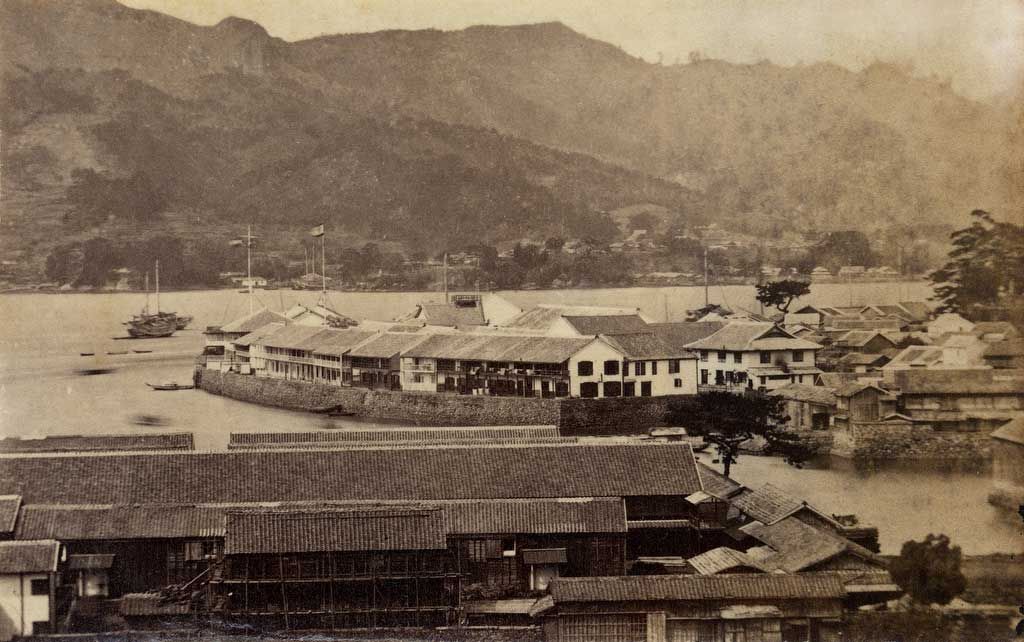

The Saga Domain’s affinity for foreign knowledge may have owed to its geographical location, encompassing most of what are now Japan’s Saga and Nagasaki Prefectures. Off the port of Nagasaki was Dejima, an artificial island that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1858). For over 200 years, it was the central conduit for foreign trade and cultural exchange with Japan during the isolationist Edo period (1600–1869), and the only Japanese territory open to Westerners.

Following the political reforms of the Meiji Restoration that began in 1868, feudal class privileges were eliminated, and Japan’s domain system was replaced by prefectures governed by a central government. Despite the profound changes in the political system, which implemented meritocratic ideals, Nabeshima became a high-ranking government official, like many of the aristocratic elite.

Before the Meiji Restoration, Japan had been largely secluded from the world for centuries. The turning point came about a decade earlier when the American expedition of Commodore Matthew Perry brought four warships to Edo Bay in 1853 and forced the shogunate to open the country to foreign trade and relations. The so-called “unequal treaties” brought about political unrest, culminating in the Meiji Restoration that galvanized Japan as a unified nation. Its new leaders were intent on achieving parity — or at least the perception of parity— with the powerful West. They resolved to urgently embrace Western civilization to prevent Japan from becoming a colony of a foreign empire, and to join the international community as a modern nation.

To these ends, the Meiji government pursued policies to strengthen the military and “enrich” the country by promoting education, industry, and commerce. A key part of this effort was a program to systematically send students abroad. Students were expected to study military affairs, politics, economics, education, and social issues, and to contribute to Japan through research and by taking leadership roles upon their return.

As the last article of the Charter Oath of 1868 declared, “Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as to strengthen the foundations of Imperial rule.”

In October 1871, the Meiji Emperor issued an edict encouraging the nobility to travel and study abroad. It emphasized that for Japan to modernize and join the international community, its people must be diligent and its nobility must visit advanced countries to acquire the appropriate knowledge. Notably, the Emperor advised nobles to travel with their wives and daughters to observe and learn from foreign educational and childcare practices.

Embarking on the Iwakura Mission

Nabeshima and his father were already convinced that acquiring broad knowledge of the world was a prerequisite for success, so much so that they began planning to study abroad a year before the Emperor’s edict. Thanks to connections with government minister Iwakura Tomomi, who was largely responsible for promulgating the Charter Oath, Nabeshima was appointed to join a landmark mission to the West in 1871. Hyakutake accompanied him — the beginning of his path to Western painting.

The Iwakura Mission sent over 100 Japanese leaders, government officials, scholars, and students on an expedition to the United States and Europe, in search of the blueprints for building a modern Japanese nation.

On December 23, 1871, Hyakutake sailed with the delegation from Yokohama to San Francisco. After spending more than six months surveying the U.S. from coast to coast, the Iwakura mission sailed from the port of Boston to continue its tour in Europe. Separating from the main delegation in Washington, Nabeshima and Hyakutake then departed on a steamship to London, where they pursued their own mission: to study at Oxford University.

Discovering art in London

Nabeshima and Hyakutake eventually arrived at the heart of the British Empire around February 1872. They settled in northeast London, staying at the residence of a British doctor. After taking lessons to improve their English, they both enrolled at Oxford University in 1873. Nabeshima took up English literature while Hyakutake studied economics. They became, along with other members of the Iwakura delegation, the first Japanese to study at Oxford University.

During his studies, Nabeshima traveled around Britain, making an effort to interact with the aristocracy and socialize as “Prince Nabeshima.” Hyakutake, who was part of his entourage, is believed to have helped organize the events and accompanied him to the venues. Nabeshima's wife Taneko also actively participated in various efforts to acquire the social skills of a “Western lady.”

Beginning in 1875 she took painting lessons from Thomas Miles Richardson Jr.; feeling uncomfortable being alone with a male artist, she asked Hyakutake to accompany her and join the lessons. Fascinated by this firsthand experience with Western art, he continued to study Western oil painting techniques while carrying out his professional duties.

Richardson visited Nabeshima's house once a week to give Taneko and Hyakutake lessons. A landscape painter like his father, Richardson exhibited at the Royal Academy and loved to paint the Italian countryside and the Scottish Highlands. For practice, Hyakutake copied some of Richardson's paintings, including Landscape with a Windmill in 1877. Hyakutake may have joined him on his regular visits to Scotland, and during a trip north in 1878 he painted Barnard Castle.

Hyakutake was in his early thirties at the time and had just started to study Western painting. But by the following year, Hyakutake exhibited one of his oil paintings, View near Yokohama in Japan, at the 1876 Summer Exhibition of the Royal Academy. Hyakutake was not only the first Japanese to exhibit at the Summer Exhibition, but also the first to show an oil painting at an overseas exhibition.

Unfortunately, the whereabouts of this painting are today unknown. Tagonoura zu (View of Tagonoura Bay), dated to 1876, might be a representative work of this period with a similar theme. There is speculation that it was the painting shown at the Royal Academy with a different title that is more descriptive to an English audience.

Paris, Rome, and a masterpiece

In 1878, after concluding his studies at Oxford and staying in England for almost six years, Nabeshima and his wife Taeko began preparations to return to Japan to assume a post at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Nabeshima may have realized that art was a valuable medium for understanding Western culture. So, remarkably, he encouraged Hyakutake to stay in Europe and further hone his painting skills. Thanks to Nabeshima's arrangement, Hyakutake moved to Paris, where he was able to devote a year to art alone. There, he studied oil painting with Léon Bonnat, a participant in the Salon in Paris and a professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

Hyakutake created some of his best and most representative works there, including Mandorin o motsu shōjo (Girl with Mandolin, 1879).

A year later, Hyakutake was recalled from Paris to Japan to receive his next government assignment. Now a career diplomat, Hyakutake was posted to Rome as First Secretary of the Japanese Legation in Italy, from 1880 to 1882. Again, he was working alongside Nabeshima, who was the ambassador. While serving as a diplomat, he studied under the painter Cesare Maccari, an honorary professor at the Accademia di Belle Arti of Rome. This was made possible through an introduction of Bonnat, Hyakutake’s teacher in Rome.

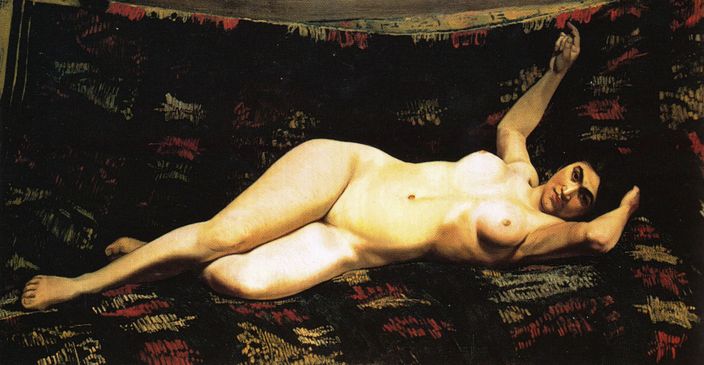

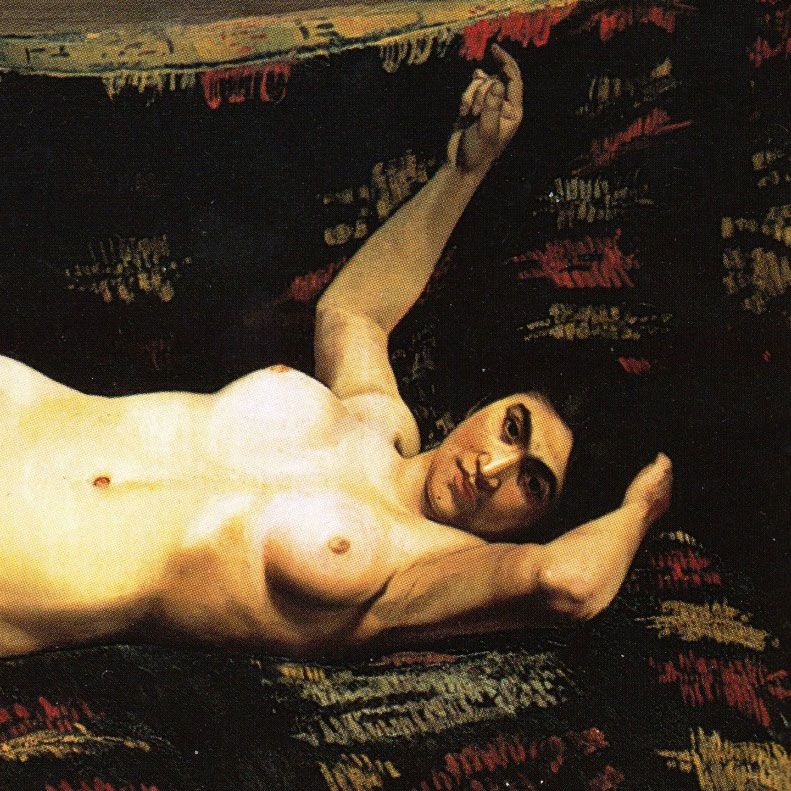

In Rome, Hyakutake completed his masterpiece: Ga-rafu (Reclining Nude, 1881), a true-to-nature portrayal of a reclining woman with a beautiful, intense presence. Along with Yamamoto Hosui’s Nude (c. 1882), it was one of the earliest oil paintings of a nude by a Japanese artist.

Another notable work Hyakutake created during his time in Italy was a portrait of Nabeshima, posing in full dress uniform, that was prominently displayed at the Japanese embassy in Rome.

Coming home with a legacy

Returning to Japan in 1882, Hyakutake became deputy director of the Trade and Industry Bureau of the Ministry of Agriculture and Trade. Unfortunately, he soon had to retire to his hometown in Saga, suffering from tuberculosis, and died in 1884 at the age of 42. He is thought to have left only a small number of works, about 40 pieces, mostly painted during his time in Europe.

Although Hyakutake was primarily a government official, his works are among the finest Western-style paintings of the early Meiji period due to the academic techniques he learned firsthand in Europe.

Remarkable as he was, Hyakutake had little direct influence on the development of Western art in Japan. For one, his prolonged absence in Europe limited his interactions with the Japanese art community. Furthermore, most of his works were painted during his time in Europe, and some of his finest creations, such as the Reclining Nude, were gifted to private individuals and remained unseen by the public for decades.

Due to unfortunate timing, there was no formal art institution to pass on his knowledge to a broader group of students after he came back from Europe. The Technical Arts School — the only academy in Japan that taught Western art — was established in his absence in 1876. It closed its doors within a year of his return, partly due to the rise of traditionalist sentiment that rejected the radical Westernization of Japanese culture.

Coinciding Hyakutake's death in the mid-1880s, Japanese painters like Kuroda Seiki traveled to Europe to study Western painting. Eventually, a new academy teaching Western art opened its doors in 1887. But by then, the European painting world was changing with the rise of Plein Air and Impressionism. Japanese artists followed these trends, and as a result, the academic techniques Hyakutake had learned lost their appeal. And so Hyakutake's work was forgotten.

Still, Hyakutake’s study of the techniques and spirit of European academicism inspired at least some Japanese artists to paint in the Western style. One of his few students, Shōdai Tameshige, also from Saga, became an active figure in the Western-style painting scene and was involved in the founding of the Western painting group Hakuba-kai, together with Kuroda Seiki and others.

Okada Saburōsuke, another Western-style painter from Saga, said that he was greatly influenced by Hyakutake’s work from an early age. He developed a strong interest in painting after seeing Hyakutake’s paintings at Nabeshima’s house at a young age, and even as a child painted pictures with shadows.

In his short life, Hyakutake Kaneyuki became a pioneer in both the art and diplomacy of 19th-century Japan precisely because he bridged those two disparate worlds. As a champion of embracing the best of Western culture, he helped the fledgling Meiji government establish diplomatic relations in Europe. And as an artist with eyes open to the unfamiliar, he led the way in bringing Western-style painting to Japan.

Details

- Family Name

百武

Hyakutake

- Given Name

兼行

Kaneyuki

- Born

June 7, 1842

Saga, Japan

- Died

December 21, 1884

Saga, Japan

- Gender

- Male

- Nationality

- Japan

- Occupations

- Painter,

- Diplomat

- Fields of practice

- Painting,

- Yō-ga

Selected

Works

Paintings

Artist

Tagonoura zu

Basha no aru fūkei

Kōsaku

Haha to ko

Bānādo-jō

Burugaria no on'na

Itariya fūzoku

Rōfujin zō

Waito shima

Sae Hime-zō

Itaria fūkei

Shōjo-zō

Tanbarin o motsu shōjo

Rafu

Gashitsu

Futsukoku heishi zu

Burugaria no on'na

Seiyō fujin-zō

Mukōjima fūkei

Connections

- Teacher of

- Shōdai, Tameshige