Art, Pan-Asianism and Arai Kampō

For nearly three months during the winter of 1916-1917, a small team of Japanese artists laboured almost without rest inside a set of caves in the Indian princely state of Hyderabad. They shared their workspace with bats, boars, wild monkeys and a leopard. To the perils of the local wildlife was added the stench of bat dung and the precariously-constructed scaffolds on which they worked. Still, they considered all this a privilege: the coming full-circle, after long centuries, of Japan’s relationship with India.

These were the Ajanta Caves, celebrated for their ancient Buddhist paintings. The Japanese artists were here to make faithful copies, inspired by a movement back in Japan that emphasised cultural connections across Asia and credited India as the source of much of the region’s religious and artistic genius. Over the next three decades that movement, known as Pan-Asianism, would lead Japan and much of mainland Asia into very dark places. But Arai Kampō (1878 – 1945), leading this historic endeavour in India, represented its early, bright optimism, which never entirely went away. He had fallen in love with Indian culture early in life, and had come to believe that Buddhist art was the highest form of art the world had to offer.

Indian ideas had arrived in Japan back in the sixth century, in the form of various schools of Buddhism travelling via China and Korea. They were followed, in 736, by the first known Indian ever to visit Japan: a Buddhist scholar and monk by the name of Bodhisena. While in Japan, Bodhisena met Gyōki, a renowned Japanese monk and philanthropist. It was later said that the two men came to recognise one another as reincarnations of people who had been present at Vulture Peak when the Buddha preached the Lotus Sutra. They had been destined to meet again like this.

While in Japan, Bodhisena also met Emperor Shōmu, in Japan’s then-capital Nara. Shōmu was a devout Buddhist, who was moved by a devastating smallpox outbreak in 735 to establish a protective nationwide network of Buddhist temples and nunneries: one of each, in every province. Tōdai-ji in Nara was to serve as the central temple for this network and its centrepiece was an enormous sixteen-metre gilded bronze statue of the celestial Buddha Vairocana. The casting of the statue required 338 tons of copper and 16 tons of gold, nearly driving Japan into bankruptcy. The honour of dedicating the statue in 752, during which its eyes were ceremonially opened, was given to Bodhisena. He performed the ceremony in front of around 7,000 courtiers and 10,000 monks. The brush he used is kept to this day in the Shosoin Repository.

Contact with India was limited in the centuries that followed, until in the mid-1500s Portuguese traders and missionaries began to arrive in Japan, during a period of bloody civil war. By this time, Portugal’s Asian empire included parts of India, including Goa, alongside a modest presence in China. Their network helped to reconnect India and Japan – though not, at first, with happy results.

Francis Xavier, the Jesuit ‘Apostle to the East’, heard from a Japanese man named Anjirō that people in Japan worshipped their god with altars, bells, rosaries, incense, statues and paintings. They were aware of heaven and hell, and they had monks who lived communally and engaged in prayer, chanting and fasting. The whole system had been founded, Xavier was told, by a holy man who had spoken of a single creator-god more than 1,500 years ago. This man had given commandments, too, including prohibitions on killing and theft, and had lived somewhere to the west beyond China.

The Jesuits were delighted: all this seemed to be proof that Christianity had somehow made it to Japan many centuries ago. They needed only to refresh people’s memories and provide a little leadership. Some of Japan’s Buddhist monks, meanwhile, were excited to meet the Jesuits. When questioned, these nanban – ‘southern barbarians’ – claimed to have travelled to Japan from India (which was true, in a sense: they had embarked at Goa). They also spoke of Dainichi: the celestial buddha, whose name the Jesuits had heard from Anjirō and which they deployed early on in Japan in hopes of building cross-cultural bridges. Could it be, wondered the Japanese, that these men came bearing new Buddhist teachings from India?

Hopes were soon dashed on both sides. The Jesuits began denouncing Buddhism and reverted to ‘Deus’ for the name of the Christian God. Some of Japan’s Buddhists took to calling him ‘Dai-uso’ – ‘great lie.’ Warlords of this era, including Oda Nobunaga and Hideyoshi Toyotomi, showed an interest in India: Nobunaga questioned one of the Jesuits at length about the country, while Hideyoshi vowed to conquer the place one day. But soon after Japan’s all-consuming civil war ended, the country’s new Tokugawa shogunate decided to close Japan’s borders almost completely. When it reopened them, in the mid-nineteenth century, it found itself with a great dilemma on its hands. It was clear that Japan had to catch up with modern western technology and institutions, from steam-power to banking and postal systems. But for allies in this new world, should it look towards Asia or to Europe and the United States?

In a newspaper editorial published in his newspaper Jiji shinpō in March 1885, one of the foremost thinkers of the era, Fukuzawa Yukichi, advised his countrymen to say ‘Goodbye to Asia’. A new spirit of ‘civilization’ was abroad in the world, he declared, associated most powerfully with the modern West. Japan must therefore turn its back – for now, at least – on the great cultural zone of which it had been a part for many centuries, and cast its lot instead with the West.

Fukuzawa’s negative view of Asia – he described Japan as like a ‘righteous man living in a bad neighborhood’ – was connected with his low view of Confucianism and Buddhism. The former was part of the hidebound traditionalism that Japan needed to escape: Fukuzawa famously derided Confucian intellectuals as ‘rice-consuming dictionaries,’ with none of the pragmatic flair that modern Japan so badly needed. The country’s various Buddhist sects, meanwhile, were accused of peddling cosmological falsities and stifling the sort of free inquiry with which the likes of Fukuzawa credited the best minds of the modern West. These attitudes carried over into the arts, where Western tastes were regarded as being superior. Attempts were duly made to reform kabuki, from a raucous all-day event to something resembling a night out at the theatre in London or Paris: people dressed up, and sat in respectful silence. Japanese art, and in particular the woodblock art of the early modern era, was meanwhile disparaged. Attempts were made instead to learn a variety of western painting techniques, and institutions were set up to this end in major cities like Tokyo.

This rather naïve embrace of the West did not last long. By the 1880s, Japanese traditionalists and neo-conservatives were fighting back. Motoda Eifu, tutor to the Emperor, once memorably declared that the only western values he could discern were ‘fact-gathering’ and ‘technique’: in other words, western modernity appeared to be premised on the successful manipulation of nature, to the detriment of true values or connection with life at its deepest levels. For some of the many Europeans who agreed with this judgement, India came to be idolised as a source of spiritual regeneration. Linguists, painters and poets all came to appreciate what they regarded as the ancient and unspoiled landscape and human genius of the subcontinent. William Jones proved that Sanskrit, Latin and Greek share the same common ancestor and thought-world. William Hodges painted the haunting Ghauts at Benares, in 1787. And Samuel Taylor Coleridge was briefly swept off his feet by Hindu philosophy.

For Japanese intellectuals and artists who began to take an interest in India in the 1870s and 1880s, there was a similar sense of spiritual longing. India was ‘home.’ It was the origin-point of Buddhism, a way of understanding and living in the world that since its introduction to Japan had come to shape so many aspects of life: worship, music, art, morals and much more besides. But these sentiments were mixed up with a powerful emerging self-image of Japan as the place where modern life met Asian antiquity. The fruits of that meeting would, on this view, be a kind of double rescue: of the West from the disenchantment and soullessness that were the price of rapid scientific and industrial advance, and of mainland Asia from the mire of traditionalism and western colonial interference.

‘Pan-Asianism,’ as this idea was known, started out as a mostly-sincere attempt to articulate what Japan, as the first Asian nation to modernize along western lines, could offer to its Asian neighbours. It was nevertheless vulnerable to exploitation by those who sought simply to improve Japan’s strategic position: the adding of Taiwan and Korea to Japan’s emerging empire, in 1895 and 1910 respectively, was pitched to the general public – abroad and at home in Japan – as an exercise in civilisational uplift.

One of the most influential Pan-Asianists within the Japanese arts was Okakura Kakuzō (also known by the name Tenshin). Deeply versed in Chinese classical literature, and a creator of Chinese poems and literati paintings, Okakura served as director of the Tokyo School of Fine Art (Tokyo Bijutsu Gakkō) and the fine art section of the Imperial Museum. In his book The Ideals of the East with Special Reference to the Art of Japan (1903), published in English and primarily for a Western audience, he offered one of the best-known articulations of Pan-Asianism in the arts:

Asia is one. The Himalayas divide, only to accentuate, two mighty civilisations, the Chinese with its communism of Confucius, and the Indian with its individualism of the Vedas. But not even the snowy barriers can interrupt for one moment that broad expanse of love for the Ultimate and Universal, which is the common thought-inheritance of every Asiatic race, enabling them to produce all the great religions of the world, and distinguishing them from those maritime peoples of the Mediterranean and the Baltic, who love to dwell on the Particular, and to search out the means, not the end, of life…

It is in Japan alone that the historic wealth of Asiatic culture can be consecutively studied through its treasured specimens. The Imperial collection, the Shinto temples, and [megalithic tombs] reveal the subtle curves of Hang workmanship. The temples of Nara are rich in representations of Tang culture, and of that Indian art, then in its splendour, which so much influenced the creations of this classic period – natural heirlooms of a nation which has preserved the music, pronunciation, ceremony and costumes, not to speak of the religious rites and philosophy, of so remarkable an age, intact…

The singular genius of the [Japanese] race leads it to… welcome the new without losing the old… It is this tenacity that keeps Japan true to the Asiatic soul even while it raises her to the rank of a modern power.

Okakura completed his book during a visit to India in 1901-2, during which he met one of India’s most famous religious modernizers and cultural nationalists: Swami Vivekānanda. The two travelled together, by train and horse-drawn carriage, to the major Buddhist sites of Bodh Gaya and Sarnath – the locations, respectively, of the Buddha’s enlightenment and his preaching of his first post-enlightenment sermon. Both had been excavated in the nineteenth century, contributing to India’s international reputation as a great spiritual centre while at the same time inspiring unfavourable contrasts between a past ‘Golden Age’ and India’s more mixed recent fortunes. For sceptical Japanese commentators, the obvious sign of the latter was that India had allowed itself to fall under colonial rule while Japan had managed to avoid that fate.

Alongside these sceptics were Japanese artists keen to forge renewed Indo-Japanese bonds. Okakura led the way, in his relationships both with Vivekānanda and with the great Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore. Okakura saw parallels between his artistic movement in Japan and the Bengali renaissance, to which the Tagore family had made enormous contributions. Tagore meanwhile recalled that it was upon meeting Okakura that the concept of an ‘Asiatic mind’ first made sense to him. After Okakura came his disciples in the Nihonga movement: a new progressive school of Japanese painting, based on traditional techniques and developed as a counter-weight to western styles. Yokoyama Taikan went out to India with Hishida Shunsō and together they engaged in a brief but important period of cultural exchange with Indian painters including Rabindranath Tagore’s nephew Abanindranath Tagore. Abanindranath was inspired by Taikan’s innovative mōrōtai technique. The word meant ‘misty’ or ‘hazy’ and its effect was akin to impressionism. It was Taikan's answer to a question that he once asked himself: ‘How can I paint air?’ Yokoyama and Hishida, meanwhile, studied Indian iconography. One of the fruits of Yokoyama’s study was his remarkable Indo shugojin [Indian Guardian Goddess] (1903), inspired by the Hindu goddess Kali and completed either in India or shortly after his return to Japan.

Back in Japan, Okakura tried to generate interest in contemporary Bengali art, via his journal Kokka (‘National Glory’). But not all Japanese critics were impressed. The archaeologist Hamada Seiryō wrote in 1909 that he saw in modern Indian painting signs of India’s ‘national agony… of scissions and submissions.’ A few years later, in 1916, an exhibition of Indian painting was held to coincide with the first visit to India by Rabindranath Tagore, whose fame had by this point increased enormously thanks to becoming Asia’s first recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. One reviewer dismissed the ‘faint-hearted sentimentalism’ on display, while the Japanese philosopher Inoue Tetsujirō reacted angrily to a lecture by Tagore in which he warned his Japanese hosts against falling into the sort of militaristic national chauvinism that was then leading Europe into the abyss – two years into the Great War. Inoue dismissed Tagore’s words as ‘the song of a ruined country’. Two years later, the influential art critic Taki Seiichi described a painting that Tagore had brought with him from India in 1916 as ‘sentimental’, ‘atrophic’ and – perhaps drawing on Inoue’s earlier comment – ‘the art of a ruined country’.

Despite these tensions in Pan-Asianism and within the Indo-Japanese relationship, Tagore’s first visit to Japan proved to be an extraordinary blessing for a young artist named Arai Kampō. Born in Ujiie, in Tochigi prefecture in 1878, Arai moved to Tokyo with his family in 1899 to study painting. There, he trained under Mizuno Toshikata, one of the late masters of ukiyo-e, before joining Okakura’s Kokka in 1902, where he made copies of ancient art and Buddhist paintings. Across ten years of doing this work, Arai came to believe that ‘Buddhist paintings were the highest form of art.’

The downside of Arai’s early career was that he had comparatively little time to work on his own art. But thanks to the sponsorship of a silk trader named Hara Tomitarō, an art connoisseur, supporter of Japanese artists and owner of a grand garden in Yokohama called Sankei-en, Arai was brought into the orbit of some of the great Nihonga painters of his day: men like Yokoyama Taikan and Shimomura Kanzan. Stimulated by some of these artists’ interests in India, and by a lecture given by the Meiji explorer Tachibana Zuichō – of which he created a sketch – Arai fell in love with India at a distance and began to long for an opportunity to see the place for himself. In the end, it was Rabindranath Tagore who gave him that chance.

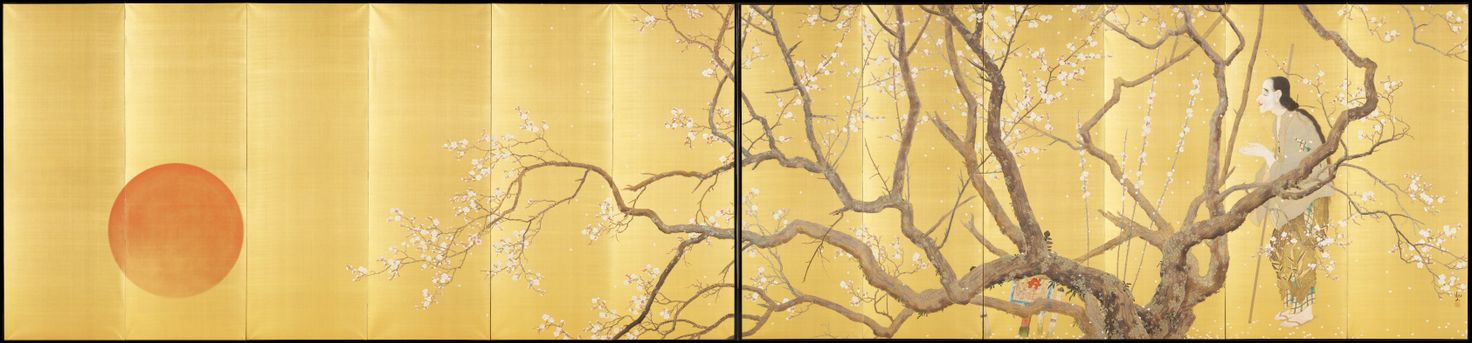

While in Japan, Tagore encountered a painting by Shimomura, called Yorobōshi (1915). Inspired by a Noh play of the same name, and consisting of two six-panel paintings, it shows a blind man named Shuntokumaru praying under plum blossoms with the sun off in the distance. For Tagore, the paintings brought to mind a passage from India’s spiritual classic, the Upanishads: ‘Lead me from the darkness to the glorious light.’ Seeing these paintings was, Tagore later recalled, a revelation ‘beyond description by words.’

Tagore asked whether it might be possible to have copies made of the paintings and sent to his home in India. His Japanese hosts agreed and Arai was charged with the task of making the copies. He moved into a pavilion within Sankei-en, and set to work copying Yorobōshi. Tagore is said to have visited Arai every day, becoming ever more impressed by Kampō’s technical skill, artistry and character. Tagore decided to invite Kampō to India, asking him to bring his copies with him and stay on as a teacher – of calligraphy and of large-scale painting, since in Indian art the Mughal-style miniature still predominated.

Arai left Tokyo in November 1916 and arrived in Calcutta the next month, paintings in hand. Somehow overcoming his lack of English or Bengali, he began teaching at Rabindranath Tagore’s educational institution: an open-air school – Arai described it as a ‘jungle school’, under a canopy of tropical trees – which went on to become Tagore University. Arai would teach in the morning and then do his own painting and sketching in the afternoons: works based on Indian legends and Buddhist tales, alongside sketches of Japanese gods and buddhas executed in an Indian style. Amongst Arai’s best-known pupils at the school were Tagore’s own nephews, Abanindranath and Gaganendranath.

Arai found time to travel around Bengal by ox-cart, meeting farmers and enjoying nature, and to develop a friendship with the Bengali artist Nandalal Bose. He made visits further afield, too: to ancient Buddhist sites across the subcontinent and down to Sri Lanka, which had the effect of deepening his own Buddhist devotion, and once with Rabindranath Tagore to Darjeeling, close to the Himalayas. There were difficult moments for Arai, during these months. Sometimes on his travels, lacking an Indian guide to smooth the way for him, he missed the comparative ease and luxury of his life back in Japan. There were times when he even went without food or drink – periods of ‘suffering’, as he later described it, which in the end were more than worth it.

Even life in Calcutta could have its ups and downs. On one memorable occasion, Arai attended a séance, at which the spirit of one of Arai’s ancestors appeared and greeted him – in English. Arai was there, too, when Rabindranath Tagore was arrested by the British, the result of the political activism that Tagore combined with his attempts to sustain a cultural renaissance. Arai recalled being greatly relieved to see Tagore return home in one piece. He clearly developed a deep affection for Tagore, regarding him as s true sage. Arai was impressed, on one occasion, to find Rabindranath Tagore and his family praying in front of the copy of Yorobōshi that Arai had made. They used words derived from the Upanishads: ‘All the people in the world stay in darkness and long for a light.’

The final period of Arai’s time in India was devoted to the task of making copies of the Ajanta cave paintings. He set out for Ajanta in December 1917 and stayed there until March 1918. The work was funded by the Kokka journal and a prominent art historian named Sawamura Sentarō was appointed to oversee it. The work itself was done by Arai, together with three other painters: Asai Kanpa, Kiritani Senrin, and Nousu Kōsetsu. The government of Hyderabad gave its permission and provided practical support for the undertaking.

The work was not easy. Aside from the risky conditions, given the rickety scaffolds in use and the animals with whom Arai and his colleagues were compelled to share the caves, the wall surfaces themselves were very fragile: made from mud and cow dung, and easily damaged. Asai, in particular, seems to have had a difficult time of it, required to lie down atop a precarious scaffold and trace the ceiling paintings by lamp-light, his own paint constantly dripping into his face.

Still, according to later accounts of the project, Arai and the others worked all day every day for nearly three months, with only two or three days’ break. Arai no doubt felt that this effort was the very least that he owed to the painters of the original works. He was clearly in awe of them, often repeating the legend that once they had completed their work they cut off their own right hands:

Such were the deep devotion and high spirit of the artists in ancient times. It is therefore not by chance that this giant work of art survives to this day. Here is the great endeavour that the Buddha-virtue accomplished. During the execution of the copy I was honoured by the chance to converse continuously with the souls of the artists of two thousand years ago. I myself also give thanks to the Buddha-virtue.

It isn’t clear whether Arai had also heard the legend that the architect of the Taj Mahal either had his hands cut off or his eyes gouged out, so that he could never create anything to equal it in its beauty. But that hardly matters. Arai was moved to tears by the end, facing the prospect of leaving the caves behind. It was also the end of a close period of companionship with his fellow workers, who together had sung songs by moonlight during their hours off, with Senrin playing the shakuhachi.

After holding an exhibition of the Ajanta painting copies at the Japanese Club in Bombay, Arai made his way home to Japan in May 1918. Before his departure, Rabindranath Tagore presented him with a poem in Bengali calligraphy:

Dear Friend,

One day you came to my room

as if you were a guest.

Today at your departure

you came into my intimate soul.

1325th year in the Bengali calendar, 25th Boishakh (8 May 1918)

Back in Japan, Arai suffered the loss, in 1923, of two copies that he had made of Descent of Demons and Bodhisattva, from Ajanta cave no.1. They were destroyed by the fires set off by the Great Kantō Earthquake. But the legacy of his Indian sojourn lived on in his own paintings. He began to create images of buddhas inspired by Hindu gods – decorated with ornaments and accessories, in the Indian style. As the years went on, and even as the pressure grew on Japanese artists to include patriotic themes in their work, Arai held on to his Indian influences. Konohana Sakuya-hime (1938), a flower goddess, is a synthesis of Asian styles. Marishiten (1941) is based on an Indian goddess linked to the sun, and includes the large halo that served as an Indian-inspired theme in a great many of Arai’s paintings.

During the final years of the war, Arai served as part of a team making replicas of the Golden Hall wall paintings at Horyū-ij temple in Nara, which had been preserved for some 1,200 years – making them some of the oldest surviving wall paintings in Japan. He had almost finished making a copy of wall no. 10, a representation of the Pure Land of Yakushi Nyorai, when he died suddenly from a stroke. It was April 1945: a remarkable time for anyone to be doing much in Japan except fighting, surviving and seeking the means to do one or the other.

Japan was on the verge of defeat, in a conflict brought about in part by the corruption of the Pan-Asian ideal of decades before. Rabindranath Tagore’s warnings back in 1916 had not been heeded. His great friend Okakura Kakuzō’s hopes for Asian unity had been dashed. But in the life and work of artists like Arai Kampō, that original spirit of Pan-Asian brotherhood and mutual curiosity had flowered and Japan’s ancient connection to India had been restored. The moment is remembered today via a Kampō-Tagore Peace Park created in the 1990s, in Kampō’s hometown of Ujiie, alongside a sister monument at Tagore International University.